While women have been a critical element of the workforce since the beginning of time, it’s only recently that women in leadership have become a holy grail for major organizations that want to be seen as open and welcoming places to work. The data is clear that organizations with significant representation of women (and other diverse leadership) on their boards and in their executive suites, regularly out-perform those with more homogenous leadership. Despite the overwhelming data that demonstrate women are good for business, organizations seeking to support women in leadership roles, not to mention the women themselves, continue to be frustrated by systemic and cultural barriers to success.

And yet, many women succeed despite the barriers put in their way. What are they doing right? How are their mentors helping them? What are their companies doing to change historically discriminatory dynamics? What are the best practices to create gender equality? In this guide to women in leadership, you’ll find a comprehensive look at the hard facts as well as the soft skills that help women become powerful contributors at the most senior levels of any organization. I’m often asked to speak and share my resources and perspectives on women in leadership. After years of culling good resources, I’ve put them into this comprehensive guide to help my clients, colleagues and connections identify good information sources and positive steps to take to help women rise to greater levels of leadership. We update this guide regularly, you’ll find the most recent version at InPowerWomen.com.

Updated February 21, 2023

Table of Contents

The Facts on Women in Leadership

There is a lot of statistical data about women in leadership; in many cases it contradicts a lot of what we think we know. What we think we know results from personal experience, cultural norms, unconscious bias and confirmation bias. The data below is not intended to be comprehensive as much as it is designed to level-set our understanding of what data should be shaping our understanding of women and leadership. This section will be updated as new data comes to light. (See something missing? contact us)

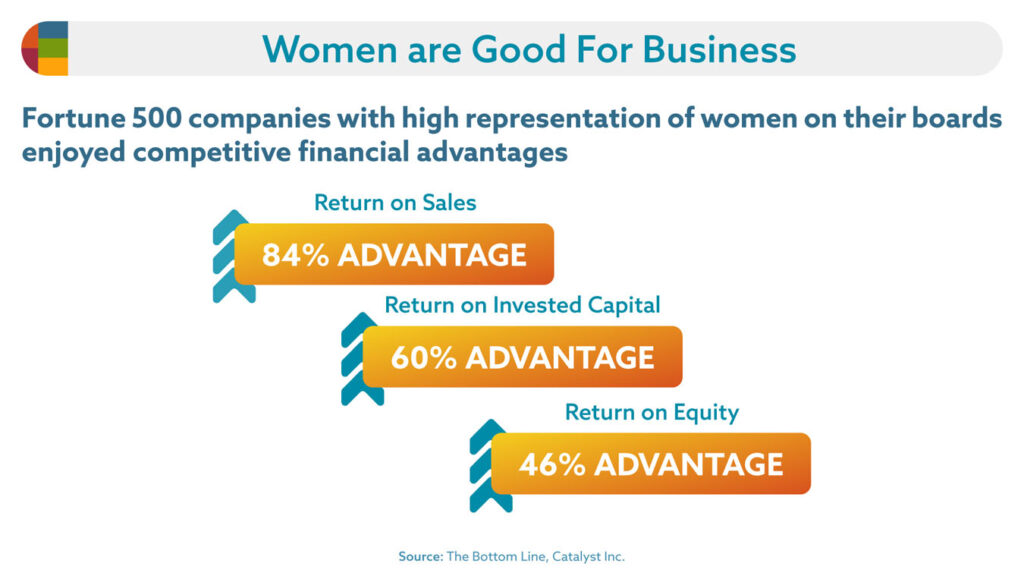

Women are Good for Business

Women in leadership are good for business. Companies with representative numbers of women in board, executive and senior management roles routinely out-perform those without such gender (and other) diversity. This performance is seen in both reputational form and in financial performance, in both good times and bad times. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the benefits of gender diversity were further highlighted. Companies with 30% or more women holding board seats outperformed their peers in eleven of 15 sectors. Despite being underrepresented compared to their presence as 50% of the population, as of 2021 women do occupy more positions of power than ever before, 31%, which takes their representation just past the tipping to higher performance. Companies around the world reap rewards from gender diverse workforces:

An interesting development in 2021 was that having met more of their gender recruitment goals over the past few years, recruiting priorities for directors shifted to emphasize racial and ethnic diversity over gender diversity. This progress in public companies is not matched by large privately held organizations, 49% of which have zero female board representation.

Diversity of all types including racial, gender and culture pays off in many ways:

- Recruiting and retaining talent

- Increasing productivity and performance

- Improved innovation, enhanced decision-making and reduced groupthink

- Improved reputation

- Reduced instances of fraud

- Improved financial performance

- Employee trust

The Glass Ceiling and the Broken Rung

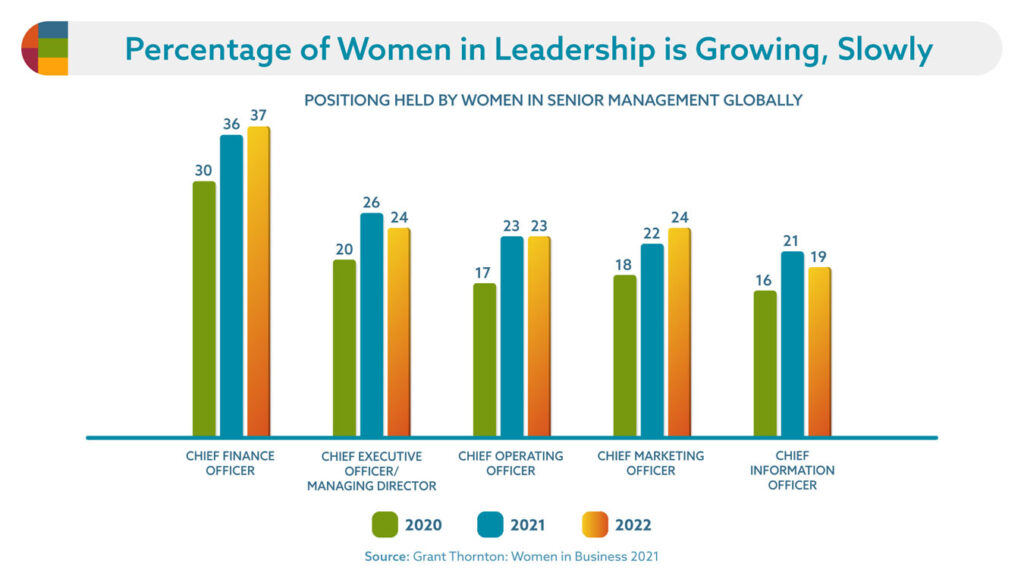

Those who follow trends relating to women in leadership will recognize the phenomenon of the “glass ceiling,” referencing an invisible cultural barrier to screening women out of top leadership positions. While this phenomenon still exists, largely due to unconscious bias that permeates most workplaces, women are making slow and steady progress into leadership positions.

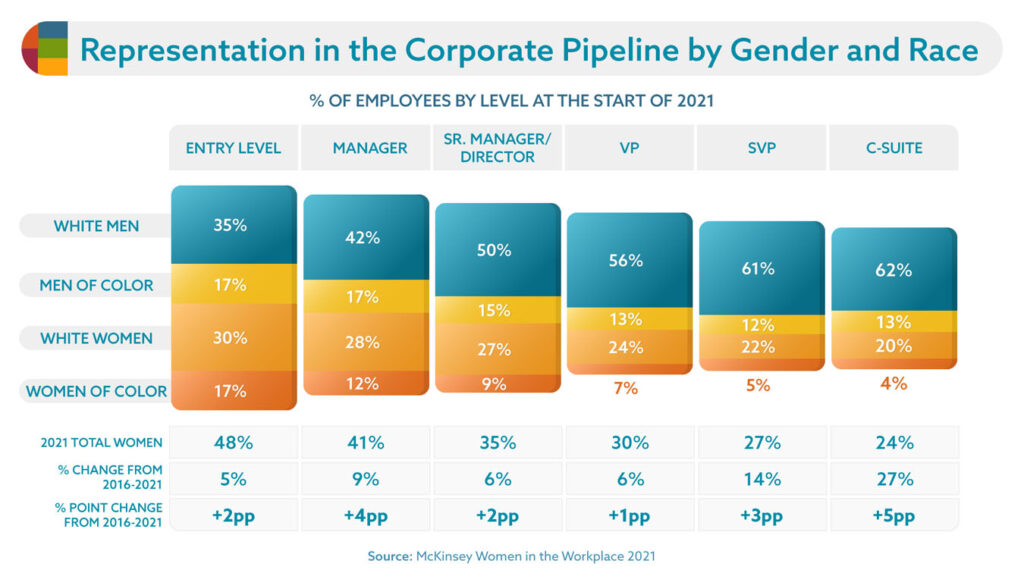

The success of women entering leadership is still tempered by the fact that their representation does not match their participation in the workforce. Women enter at roughly equal numbers to men, however, over the course of their careers they become a shrinking proportion of those fulfilling leadership roles. There is one critical drop-off point of women’s participation in leadership, which begins early in their careers.

Source: McKinsey Women in the Workplace 2022

Recently dubbed The Broken Rung, the data shows that between first and second tier management positions we see the largest drop (23-28%, varying by racial category) in women’s participation in leadership, a percentage reduction that does not recover as these aspiring leaders mature throughout their career.

While much attention is paid to The Glass Ceiling, a cultural bias phenomenon that excludes women from executive and board positions, The Broken Rung of emerging leaders is the most significant systemic challenge to bringing women into higher tier leadership positions because it shrinks the pool of available female managers with the experience to lead at higher levels.

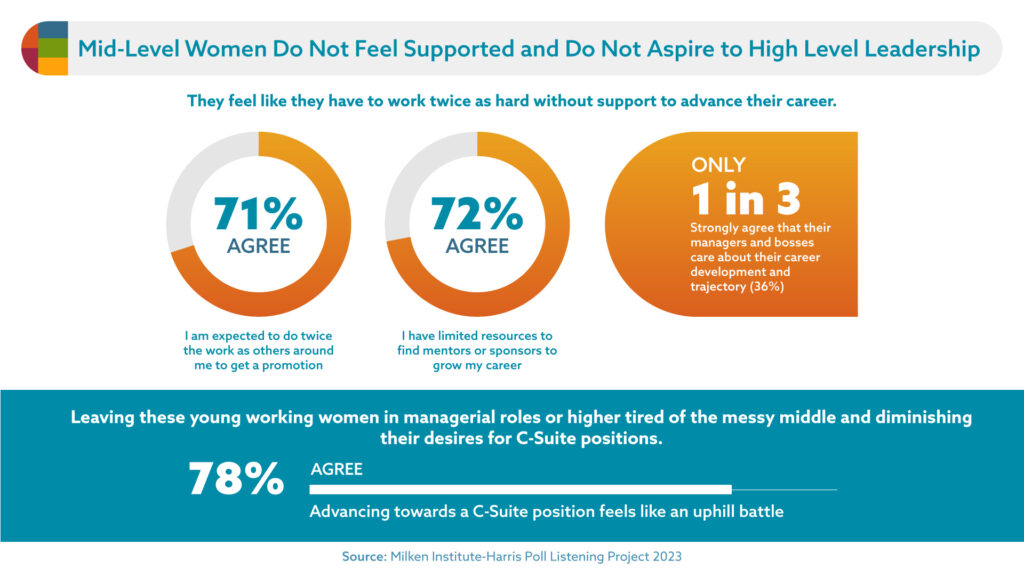

In fact, the experience of women in middle management is alarming. A significant majority of mid-level women (over 60%) do not feel supported in their career development, workload management or resource allocations, significantly reducing their interest in aspiring to top level leadership positions.

Source: Milken Institute-Harris Poll Listening Project 2023

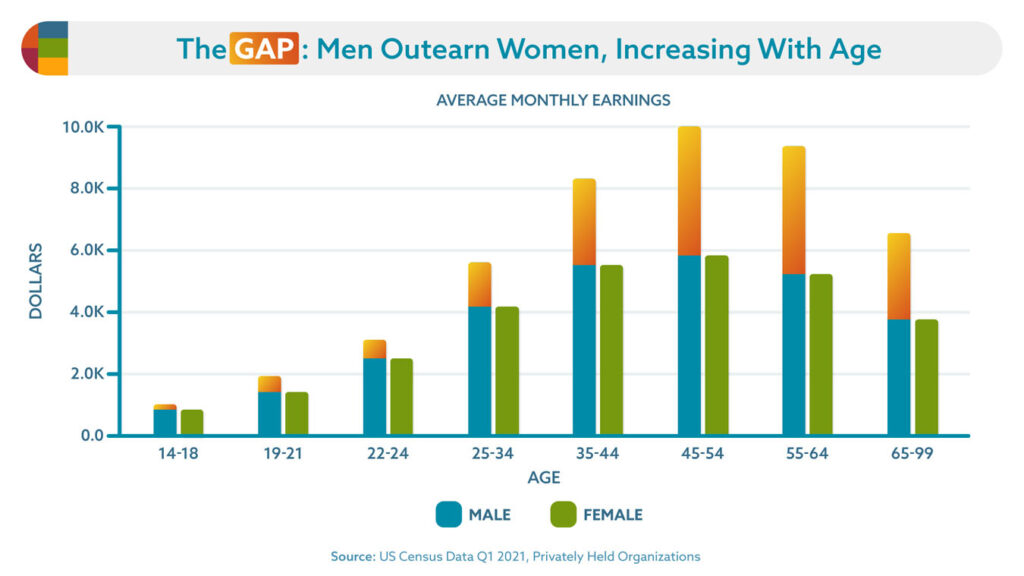

The Gender Pay Gap and Wealth Gap

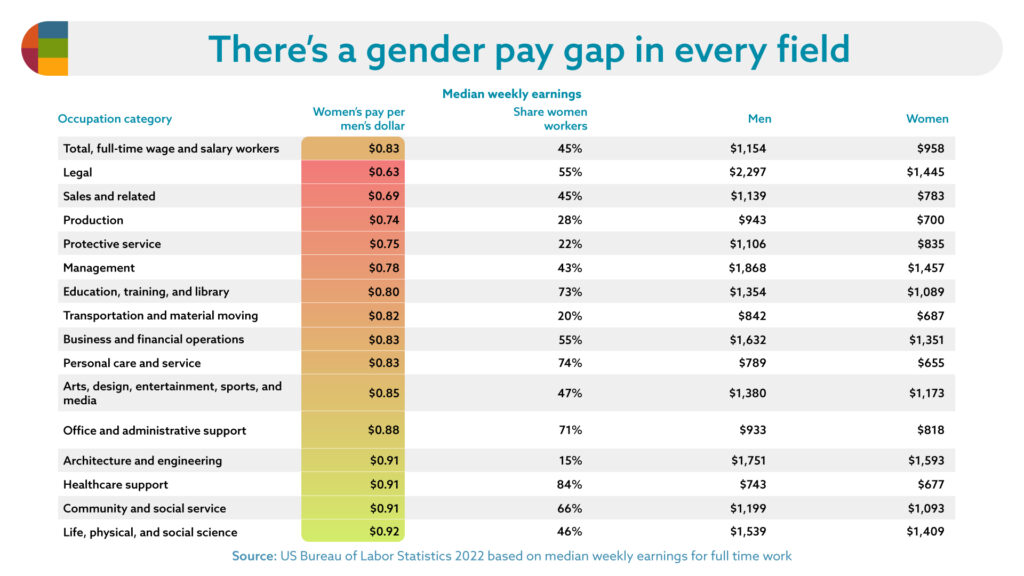

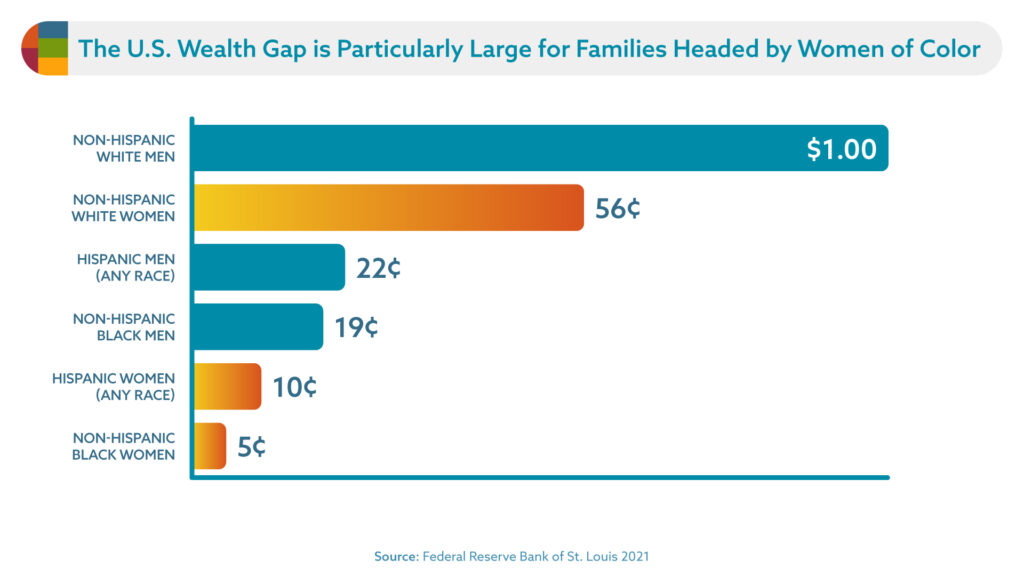

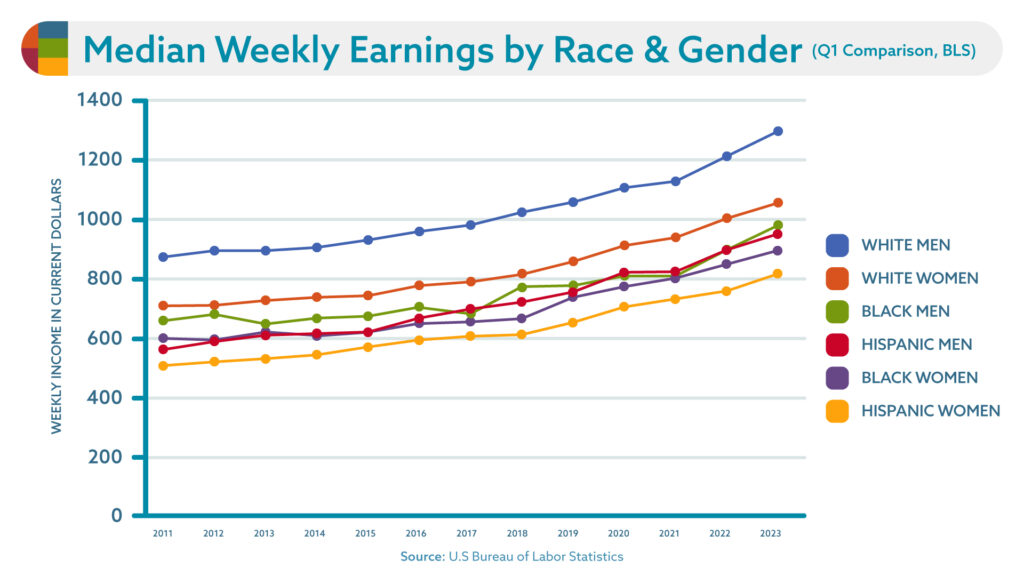

There is ample evidence that women leaders perform as effectively as men, particularly in a crisis. In 2022 amidst The Great Resignation, younger women began to out-earn men in selective geographies. And yet, the overall gender pay gap persists, with women continuing to be over-represented in low paying jobs and experiencing increases in wage disparity as they age. These trends are consistent globally. Using data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Women’s Law Center reports that in 2021, across all occupations, women make 17% less than men, and depending on the type of occupation, as much as a 45% wage gap may exist. These gender equality disparities magnify when factoring in race: Black women make only 63 cents on the dollar, and Latina women 55 cents. The pay gap for women of color is closing painfully slowly, estimated to meet pay parity in the year 2451 if the current pace continues. Most concerning? The pay gap widens as women advance in their careers, which has implications for women seeking the highest-level leadership roles.

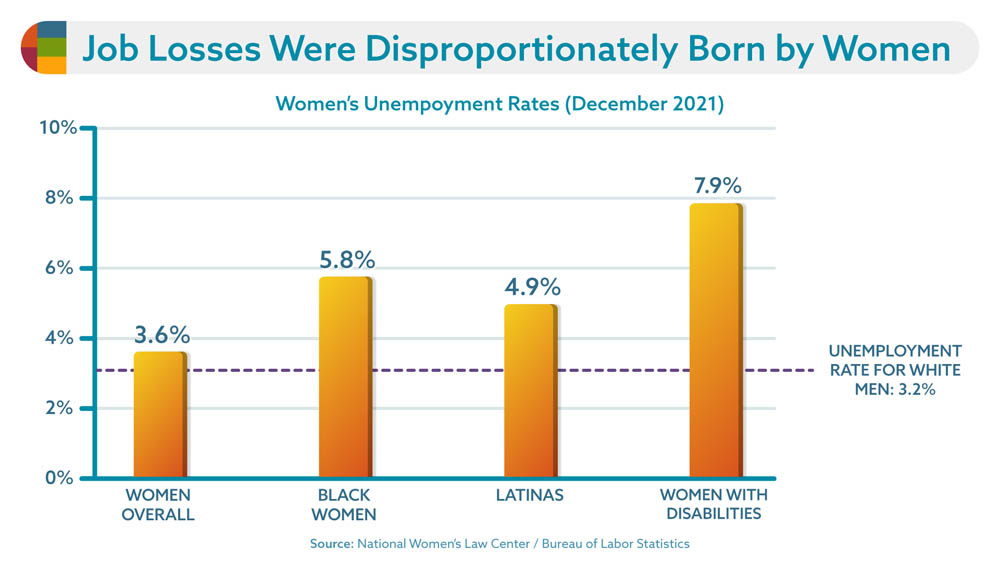

The impact of the COVID pandemic major market disruption was mixed when it came to gender impact. While the wage gap has remained relatively stable in 2021, women have left the workforce in higher numbers than men. This new participation gap (an 8% drop since 2019) is particularly notable for women without a high school education, however most education levels report reduced female participation. The resultant career interruptions, while not affecting the wage rate itself, will definitely affect these women’s lifetime income. By 2023 women’s workforce participation (77%) is essentially back to pre-pandemic levels.

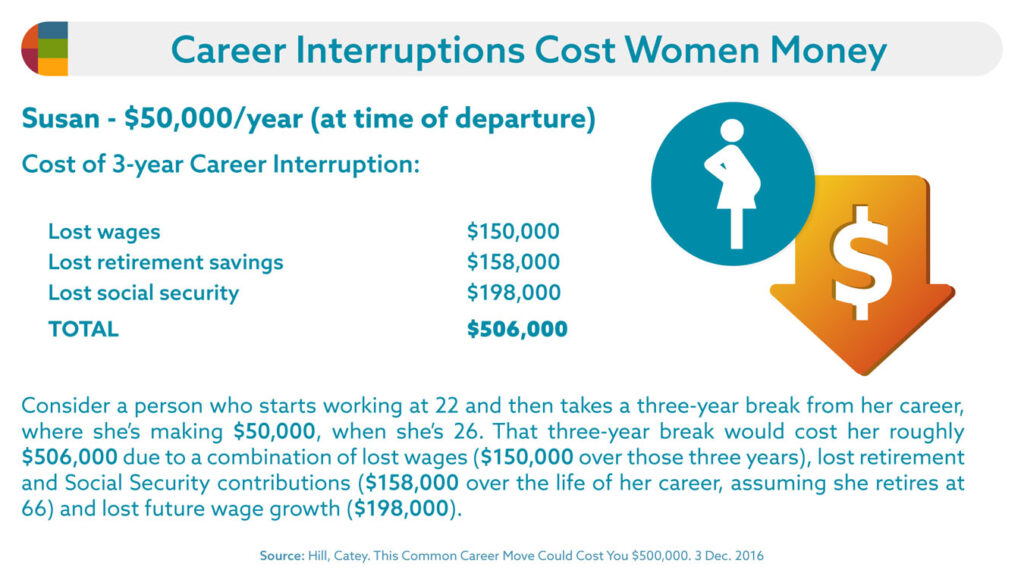

The pay gap leads to a general wealth gap for women as compared to men, which is larger than the pay gap. Globally across all job levels, women accumulate only 74% of the wealth men do and surprisingly, more senior women experience a greater gap (38% compared to 11% for front line workers.) However, it is not the only factor that depresses women’s lifetime income. Since women bear the burden of elder and child care more than men, they are more apt to leave the workforce for periods of time, which reduces their lifetime earning dramatically, and in hard dollars. A woman earning $50,000 at the age of 26 who takes a three-year career break to support a child or parent could lose over half a million dollars in income over the course of her life. Recent research puts this into context by findings that women lose on average $295,000 in lifetime earnings due to caregiving requirements that cause them turn down promotions or leave the workforce entirely for periods of time.

Source: 19th News

There are many reasons for the gender pay gap, and lack of attention to the gender wealth gap, including cultural myths such as ‘men need higher salaries to support their families’ (as though women’s children don’t need as much financial support as men’s) and ‘women don’t work as hard because they’re caring for their children’ (even though men also care for children and not all women have children). Another reason for the gender pay gap is a general lack of pay transparency policies and practices at most private organizations, which would give leaders greater insight into diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) dynamics in their organizations while also providing employees equitable negotiating power with employers.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2021

Although there are legal protections for women that prohibit wage suppression based on gender, it’s more often likely that discrimination is a function of unconscious bias (see below). Any woman who suspects she’s facing wage discrimination based on her gender should consult with the EEOC or an employment attorney to review her options.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Systemic Unconscious and Gender Bias

Most organizations and leaders want to believe they operate in a meritocracy, an organization that rewards excellent performance regardless of the gender, race, ability, thinking style or sexual orientation of the performer. Yet the data is clear that unconscious bias wires the human brain to favor and emphasize some information, including information about people’s gender, color and other attributes, in a variety of predictable (and less predictable) ways. The result is that humans are unable to see each other in fair and unbiased ways without making the effort to do so. Thus, we cannot hope to reward people based on merit alone without taking significant measures (such as pay transparency) to counter our inherent, natural and human biases.

Cultural biases represent shared personal biases, and those that disadvantage women in the workplace mean leaders, colleagues and women themselves tend to discount a woman’s contribution, attributing it to luck more than skill or effort.

Unfortunately, biases against women have been very slow to change. Globally 90% of people (women and men) exhibit biases against women, a number that has not changed in ten years.

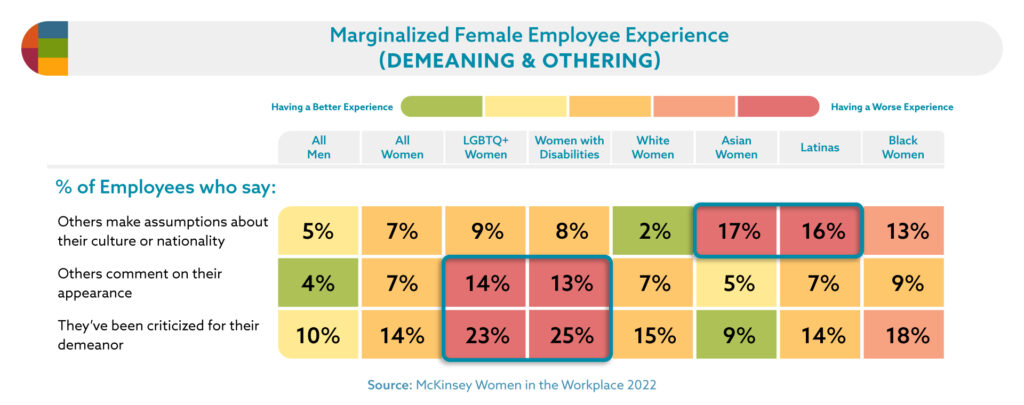

Interestingly, simply having more women in a workplace does not automatically counter workplace cultural biases that disadvantage women themselves. Although biases, and their impacts vary by industry (including those where women represent a majority of the workforce) women still experience many biases, such as:

- constrained communication, in which women must be mindful when expressing authority and downplay their accomplishments.

- lack of acknowledgement for their contributions

- assuming they’re not leaders because they’re women

- being interrupted by men when speaking

- a boys’ club mentality where decisions were made mostly by men

- a glass cliff, being held responsible for problems outside of their control

- lacking in mentors and sponsors

- receiving less actionable feedback than men

- workplace policies that make them limit their career aspirations due to personal obligations

- Age biases that penalize women at every age when they aspire to leadership positions

- the “double bind” of gender leadership expectations, a paradox for who are expected to conform to both male and female behavioral norms, associated with leadership—which are often contradictory (e.g., aggressive vs. nice, strong vs. soft and advocating for others vs. advocating for themselves.)

- Unchecked cultural tolerances of “toxic masculinity” and “fragile masculinity”that impinge on women’s ability to advance as easily as their male counterparts.

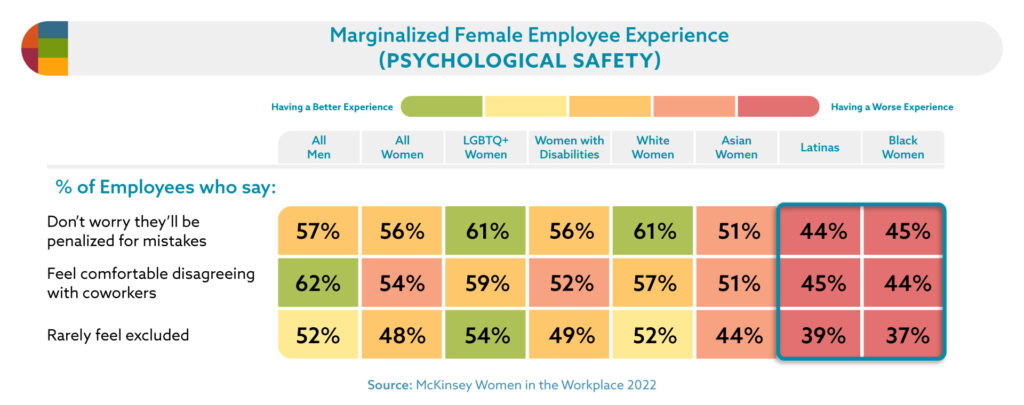

They are guided to be less aggressive and smile more. However, when they follow this advice, they are often penalized for being not aggressive enough and too nice to be an effective leader. This leaves women feeling in a no-win situation and 41% more likely to experience their workplace as toxic than the men around them.

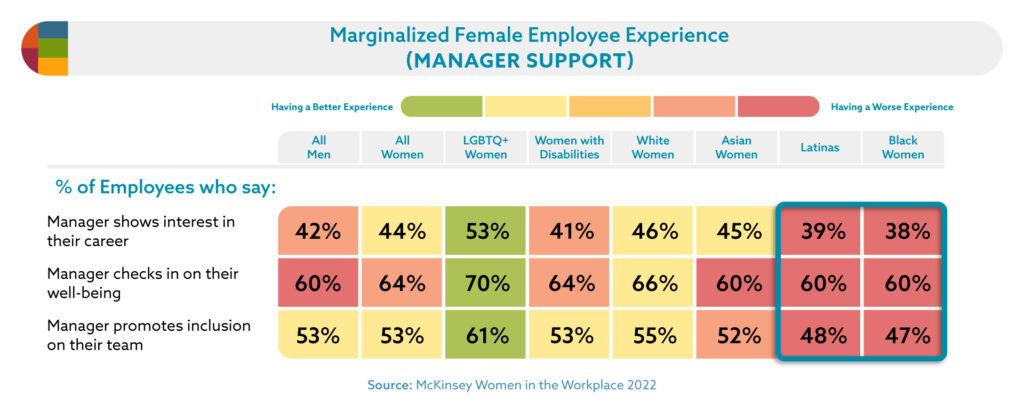

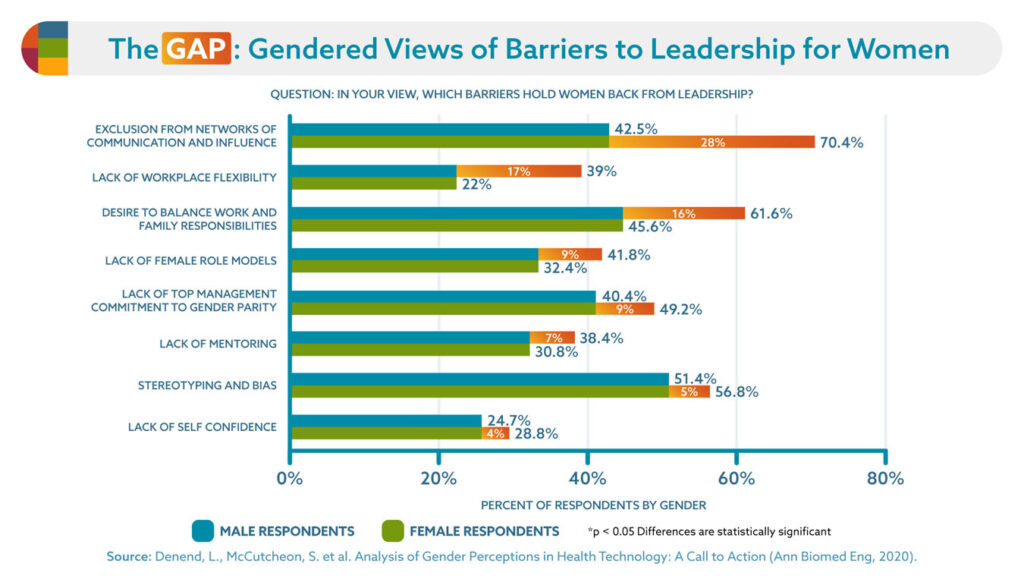

This situation is exacerbated in many ways. First of all, women’s and men’s experiences of workplace culture is so different that they also perceive the problems women encounter as they work to get into leadership very differently. This can make it hard for men to effectively mentor women, and people of color around the kinds of bias issues they encounter, and even go so far as to discount them entirely, making women question their own perception and experience. Similarly, many efforts to help women get into leadership—promoted by both women and men with good intentions—often focuses on fixing the women instead of shifting the culture in ways that would hold men more accountable for their behaviors.

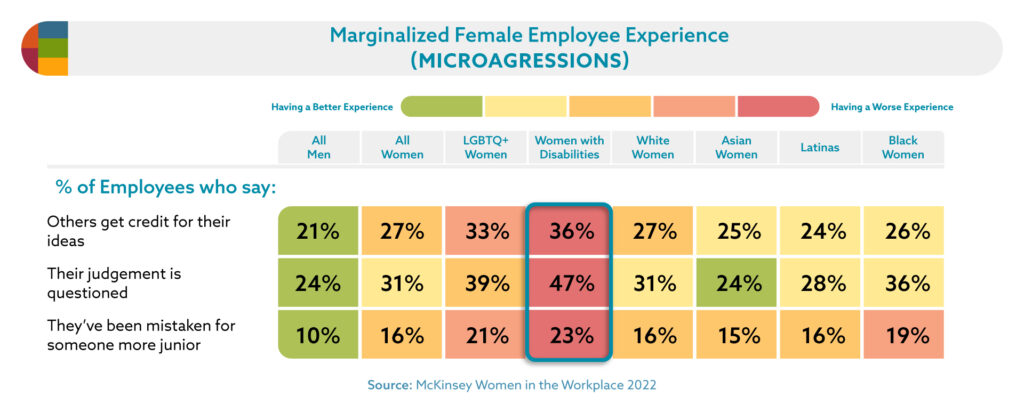

These kinds of biases are also evident in certain reverse trends. When the culture is “leveled” to put less emphasis on appearance and presence, such as in remote/hybrid work, under-represented workers may actually feel less stress. For the women leaders in the double bind, all this feels exhausting and unfair. For everyone else it’s an excuse not to deal with their own unconscious bias that puts women in the no-win scenario. In fact, the kind of bias that puts women in a double bind, is even more nuanced and affects different groups differently. Black and disabled women, for example, experience more bias-based challenge in the workplace than white women.

Like people of color, who encounter biases in the workplace which are imported from the broader culture around them, women also experience more generalized biases related to their age (including health issues related to menopause), life stage and body type. Weight discrimination in particular penalizes women, as it’s been found that for every 6 pounds gained by a woman, her salary drops $2 an hour. And like people of color, ethnic and other under-represented groups trying to fit into the dominant culture, women often feel the need to code-switch, which creates additional levels of stress, and can lead to feelings of inauthenticity.

The way to address these biases for everyone is to learn to see bias and find alternative ways to judge women authentically. Not an easy task, but one worth pursuing.

It is important to recognize that unconscious bias is a human phenomenon, that women carry bias just as men do and that men encounter biases just as much as women do. Because humans carry gender biases with them everywhere they go, such biases become pervasive in the culture, even making their way into the systems we create, such as artificial intelligence and personality tests, both of which we rely on for gender-neutral information.

These cultural biases show up in ways that affect all genders. Many male leaders often feel more cultural pressure to be aggressive and competitive than they believe is healthy, while women feel pressure to “be nice,” even when the situation calls for more disciplined expressions. However, while biases are experienced by both genders, because the “male standard” is reinforced at a cultural level, they work systemically against women seeking leadership roles in multiple ways. These biases often perpetuate myths about why women do not get into leadership, and they affect women at all levels. For example, female CEOs face greater scrutiny and longer wait times to be appointed to the top job than their male counterparts.

Most cultural myths assert that whatever reason a woman is not getting ahead is caused by a deficiency of the woman. For example, “women don’t ask for raises often enough” is cited as the reason women don’t receive equal pay. In fact research shows that women do ask as often, but don’t receive pay increases as frequently as their male counterparts. The bias that perpetuates the myth, making us believe it’s the woman’s problem when it’s not, also perpetuates the inequity.

Allowing gender bias to go unchecked and unchallenged perpetuates a general belief in society that stereotypically male leadership behavior is “good” and “desired,” and that everyone who doesn’t meet it is “lacking” and “at fault” for their own inability to advance. Of course, both women and men have personal responsibility for becoming capable, strong leaders. However, with bias present the amount any individual can do themselves to improve their odds becomes distorted, leaving women with a heavier burden of proof. By contrast, when the cultural bias and stereotypes begin to shift, everyone who is deserving of leadership can more clearly see how they can personally grow and change to achieve it. With less unconscious bias, a true meritocracy becomes more achievable.

Parenthood, Pandemic Hangovers and Mothers in the Workforce

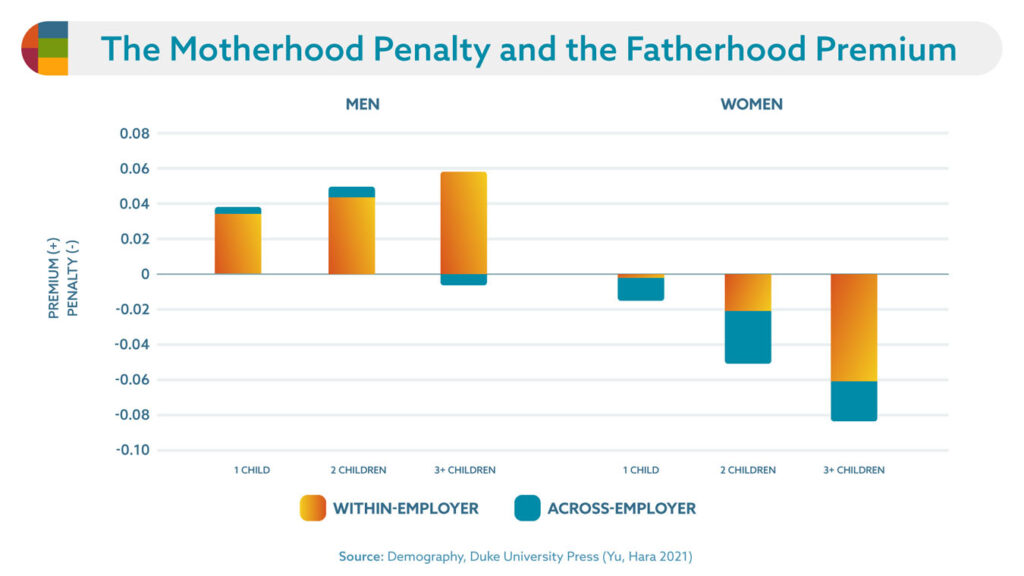

Unconscious bias also plays a role in the ways mothers and fathers are treated in the workforce. Data shows that the more children they have, mothers pay a price in several ways, such as reduced pay, fewer promotion opportunities and negative assumptions about their loyalty. By contrast, men see increases in many tangible benefits as well as preferential treatment (as compared with childless individuals.) Women experience this penalty more severely if they go to another employer whereas men see relatively little difference whether they stay or move. It’s important to note that while this works to men’s favor in terms of pay and position, it may penalize them on more invisible measures, such as support for time and travel flexibility to accommodate their family responsibilities and cultural acceptance by their male peers. They are often told to “man up” to working longer hours instead of attending their kids sports games, whereas women may receive more understanding.

It is often anecdotally assumed that when women have children, they leave the workforce or exit their career paths. In a healthy, pre-pandemic economy, this was most often not the case. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2019 a vast majority (72%) of women with children were either employed or seeking employment. However, in 2020, due to the impact of the COVID-19 virus, both mothers and fathers reduced their participation in the labor force, and while mothers and fathers both experienced an increase in unemployment, mothers were more likely to be unemployed than fathers.

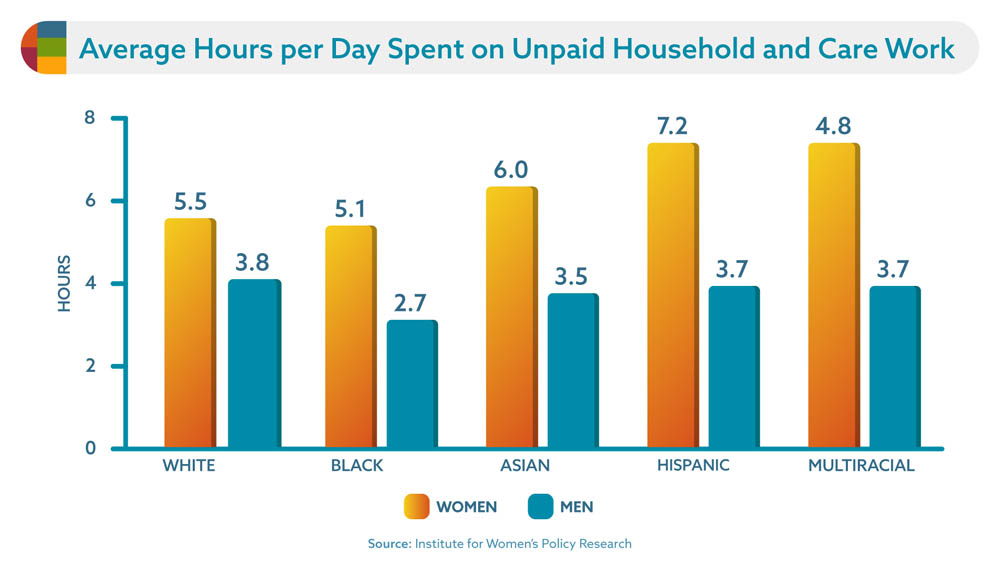

In 2021, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) characterized global growth in unemployment as a “momcession” because women’s work losses (higher than men’s) were driven largely by mothers choosing to leave work to care for young and school-age children at three times the rate of men. Even when mothers continued to work and fathers did not, women continued to bear the brunt of caregiving and other “unpaid work” to maintain the home and family.

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, working families in the U.S. lost the support of schools, daycare and other community and family support systems. As working parents struggled to balance full-time childcare and virtual classrooms, most childcare duties fell to mothers, and some women have chosen to leave the workforce rather than leave their children unsupported. While the full statistical impact of this social phenomenon is still coming into focus, based on available data it appears that women have left the workforce in far greater numbers than men. As of early 2022 it appears that men have regained their labor force losses since 2020, while there are 1.1 million fewer women in the workforce than there were in the same period in 2020.

The pandemic brought long-held inequities between working women and men into sharp relief, demonstrating the extra burden women hold in caring for children and the home (approximately 2 hours a day more for women), in every age and ethnic category, whether they work outside the home or not. Study after study shows that both women and men believe it’s appropriate for women to handle more “invisible work” at home. According to Pew Research, “Even when earnings are similar, husbands spend more time on paid work and leisure, while wives devote more time to caregiving and housework; and for women are outearn their husbands, they still do the same amount of household tasks as their husbands.”Particularly in American households, married women spend nearly twice as much time on household and child-related tasks as their husbands. Finding effective ways to meet the demands of a professional life and a personal life is a challenge every working person juggles.

This social expectation extends to the workplace as well, primarily in the form of “non promotable work.” Workplace biases that view women’s contribution to non-promotable work as more important to the team than men’s contributions place an unfair burden on women, while freeing up men to focus on tasks that will advance their career.

Both male and female managers ask women to volunteer for non-promotable tasks 44% more often than their male peers. Yet when a woman complies it can put her in yet another double-bind situation where, if she refuses, she can be perceived as more competent, but less of a team player. This demonstrates a distinct preference for women who accept non-promotable work, thereby threatening to make them more likely to overworking and burning out.

Women more often struggle with work-life balance because they, their colleagues and families, have acculturated to the assumption that women should take on the invisible work of the default fixer of personal challenges while men are the default fixers of business challenges. When she’s aspiring to an executive role, then, she’s usually trying to be seen as a reliable fixer of business challenges while also meeting her own (and others’) expectations that she will be the reliable, default fixer of personal issues as well. This problem haunts single and married women, mothers and non-mothers alike. For mothers, however, there is no getting around the additional physical requirements that birthing and caring for young children puts on them when babies come into the world.

While men find work-life imbalance a challenge to navigate just as women do, men find more cultural forgiveness when they drop a ball at home, and they also pay a lower price at work. This social inequity leads more women into a no-win scenario between overwork and burnout.

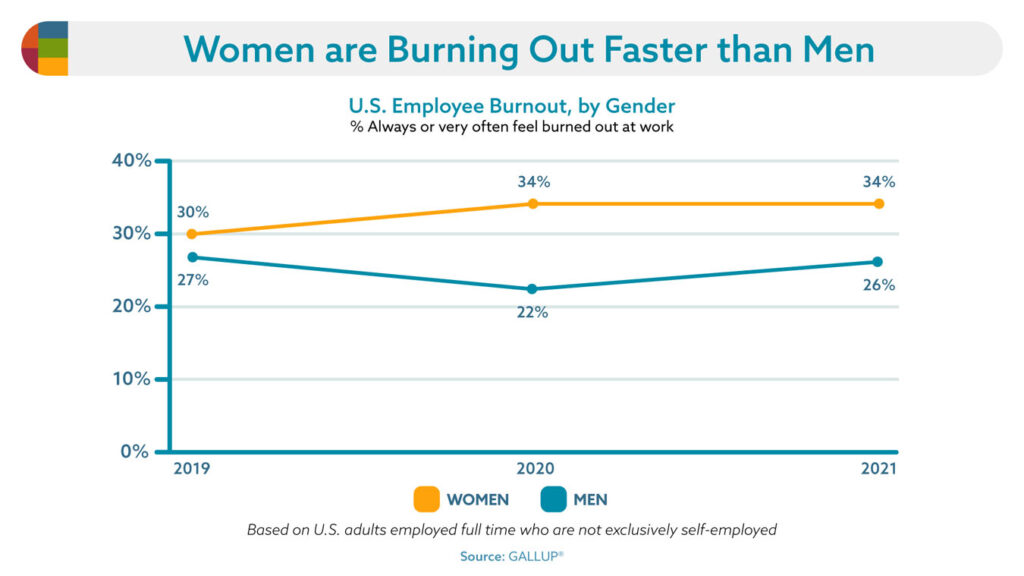

While the history of COVID-19 pandemic is still being written, it’s clear that women are more stressed about their children than their partners and are experiencing burnout at higher rates than men. And, though women have recovered the job losses they experienced during the pandemic itself, many are responding to continued stress by leaving or switching jobs more often.

Sexual Abuse, Harassment and the #METOO Movement

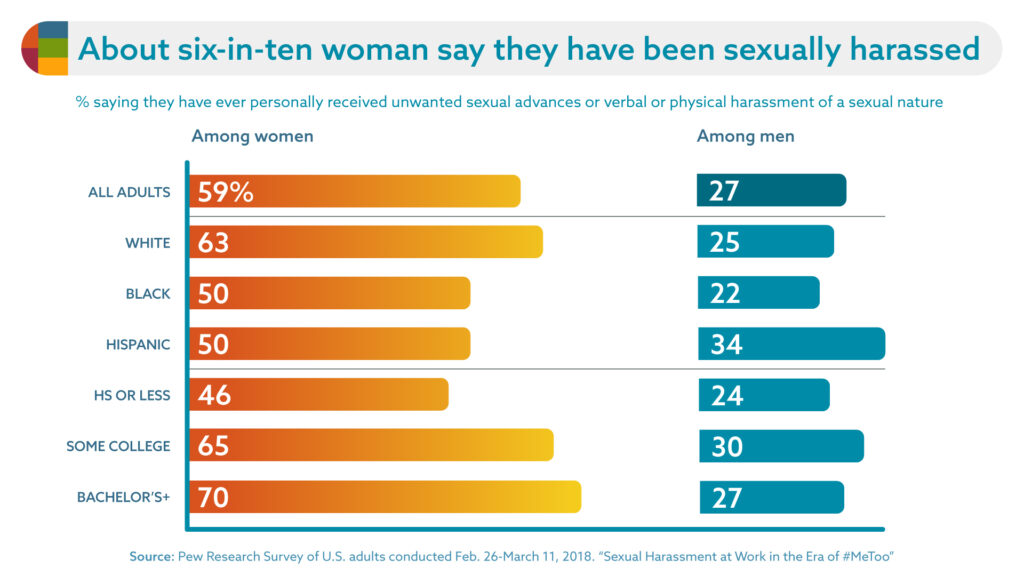

While Anita Hill put workplace sexual harassment on the front page in 1991, it wasn’t until 2017 that sexual harassment and abuse in the workplace has truly come into the modern zeitgeist. With the high profile cases of powerful men like Harvey Weinstein being taken seriously by the media and law enforcement, The #MeToo Movement’s recent reboot has had a few tangible impacts on policy, but it’s less clear that the number of women harassed has gone down significantly. In part this is because, having been put on notice that predatory gender-based behavior in the workplace will no longer be tacitly accepted by women, many senior men have become reluctant to mentor women for fear of being accused of inappropriate behavior. This #MeToo Backlash is a sad state of affairs for women in leadership. While the #MeToo Movement has made the topic of workplace harassment more talked about, and acknowledged by men, the subject is as old as time. Despite a few decades of laws meant to protect women from inappropriate behavior at work, 69% of working women still report experiencing harassment and 72% say they don’t report it. This means that almost 50% of the women in your workplace, have experienced harassment and chosen to stay silent about it.

Source: Pew Research

The solution to this still-too-often-unacknowledged and too-often-tolerated injustice in our workplaces is multi-dimensional, requiring both organizational leadership as well as victim advocates to speak up. Women seeking leadership positions are often in the most difficult situation, wanting to advocate for themselves and other women while also very aware that in speaking up they may be retaliated against through subtle means, including having their coveted leadership opportunities withheld from them.

Women in leadership positions do have options to help shift a toxic-to-women culture, including becoming a trusted mentor on these topics for younger women in the organization and an advocate for effective policy approaches. However, for change to truly happen, the most powerful women and men in the company have to make it clear to everyone that any harassment perpetrated by men, or punishment of women who refuse to accept the abuse and/or to stay silent about it, will be swiftly punished in a meaningful way.

Gender Equity Practices that Work

While many women face challenges such as pay inequity, unconscious bias and lack of family-friendly workplaces, organizations can implement policies and practices to help achieve greater gender balance in leadership. United States’ companies tend to rank poorly in global studies.

The problem is multifaceted, as are the solutions:

- Hiring women into senior leadership positions, which mitigates stereotypes and even evolves the vocabulary used to talk about leadership within an organization (Note that the presence of women in the larger employee pool does not have the same effect.)

- Goal-setting to bring more women into management positions, benchmarking and collecting data to demonstrate progress in candidate pipelines and hiring

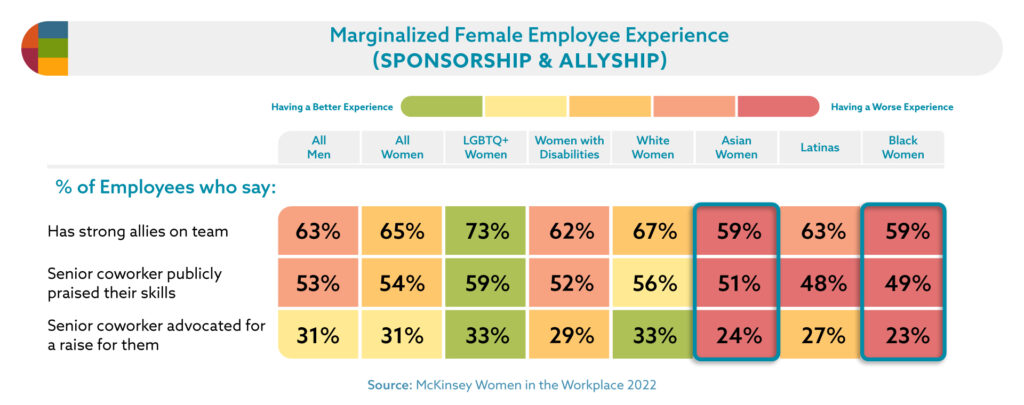

- Intentional sponsoring, mentoring and coaching of high-potential women to help develop their career and skillset for leadership jobs from early in their career to the C-Suite

- Improving hiring practices, for example to utilize joint evaluation, anonymous application screening and gender-neutral job postings, designed to remove the potential for unconscious bias to impact candidate selection

- Offer work-life support benefits such as flexible work policies that favor employee caretakers’ of both genders to improve employee satisfaction and retention, and support company’s goals to improve diversity, equity and inclusion goals more generally

- Gender-neutral behavioral guidance and recognition for managers at key employee relations points such as performance evaluations

- Fighting unconscious bias within corporate culture through leadership-led culture change to help everyone, including white men understand that fighting bias, sexism and racism in the workplace benefits them as well as others

Mentoring Advice to Help Get Women Into Leadership

The unwritten rules of business affect women’s opportunities and understanding of how they can gain leadership positions and succeed there. Although many women do receive some form of mentorship, many do not. In addition, as many women still struggle to navigate unconscious bias, and the dynamics that stems from it, so do their mentors. The information below is intended for both women seeking mentoring and the mentors themselves. When mentors—women and men—gain a deeper understanding of what truly helps women succeed in their leadership journeys, they will become more effective at helping them.

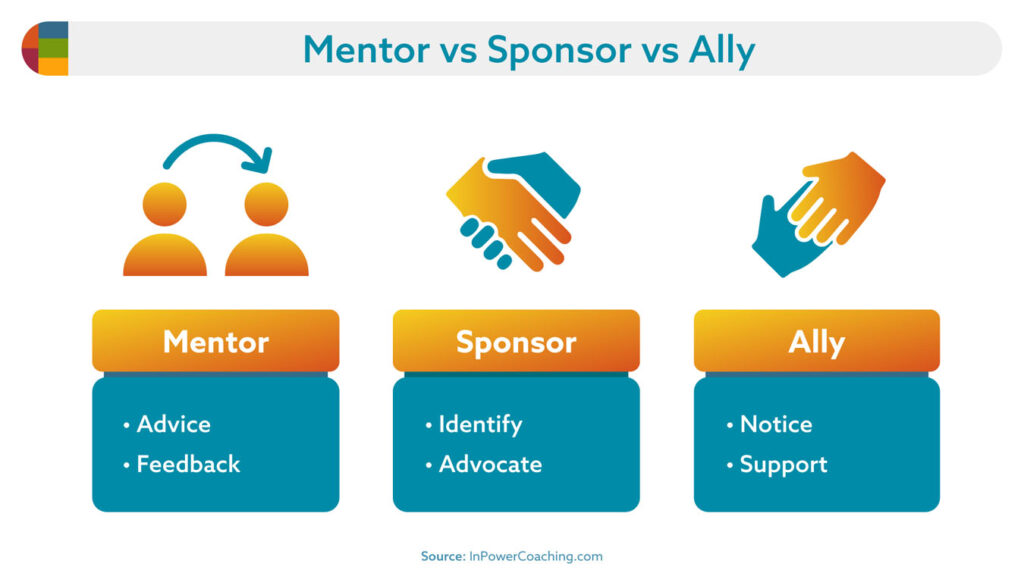

Mentor vs Sponsor vs Ally and the Importance of Visibility

Mentorship

Mentors have always been important to anyone’s success in business (and life!) It’s through mentorship we learn the unwritten rules and particular dynamics of our circumstance and culture. Traditionally men have received more mentoring than women in the workplace. A mentor’s role is to:

- Offer advice based on experience and maturity

- Provide insight and information the protégé doesn’t have access to

- Provide feedback and suggestions on development

- Make introductions that expand the protégé’s network

- Act as a sounding board to validate, expand and help problem-solve the protégé’s understanding of challenges

- Encourage and help the protégé appreciate their strengths

Mentors help fill the knowledge and perspective gap that people don’t receive from their education and direct line of management. With the realization of ways in which mentoring helped men, greater efforts have been made to give women the kind of formal and informal mentoring men have long received. Yet, even as women received more mentoring support (and learned key mentoring lessons along the way), mentorship alone has not significantly closed the gap in leadership or pay that was expected.

Groundbreaking research by Catalyst Inc. illuminated the reasons for the remaining gap, revealing a key distinction between the individuals that rise to the top and those who don’t. Thanks to this research, we now understand that both mentorship and sponsorship are important to help rising high potential leaders of all genders succeed.

Sponsorship

Being a sponsor is altogether different than being a mentor (though sponsors can certainly be mentors). An important requirement of being a sponsor is that one has influence within an organization and the ability to advocate for promising talent behind closed doors when key assignments are decided. A sponsor’s role is to:

- Identify high-potential talent

- Create opportunities for them to receive assignments that expand their capability

- Put their own reputation on the line in advocating for them to receive key assignments

While high potential women and men often know that a sponsor is working for them behind the scenes, just as often they don’t. And whereas a mentor relationship is generally very personal and mutual, relationships with sponsors can be more distant. Similarly, while mentors and protégés tend to choose each other, sponsors choose who they wish to support, based on who they see making high-profile and high-value business impacts.

The bottom line for women seeking the executive suite is that to gain sponsors who will go to bat for them to receive important assignments — assignments that build executive mindset and broaden understanding and ability to impact the business — the women need to become visible, personally and through their professional accomplishments. Through such visibility, women can “get on the radar” of sponsors who can open doors and create career-defining opportunities.

Allies

Allies are yet another group who can support women seeking greater leadership responsibility. Allies can be mentors, sponsors, managers, colleagues, peers and even staff who believe in a woman’s potential and find ways in the daily course of business to help her gain visibility and recognition. Allies are particularly important for their ability to help people overcome cultural barriers to success brought on by their gender, race, socio-economic status or any other aspect of unconscious bias. Allies also model positive behaviors for others by visibly countering bias.

Apparently men are more likely to believe they’re being good allies, than the women they are trying to help. However, when men—especially men in power—are trained as allies and become effective, they can be very helpful, primarily because they won’t be penalized the way women and lower ranking men may be, for speaking up on behalf of women.

Ally behaviors can be confrontational but are more likely to be effective if they are not, and simply conducted in the daily flow of business, thus normalizing anti-stereotypical behavior towards women and other under-represented leaders. Ally behavior can appear in many ways, including:

- Asking a woman hesitant to speak up in a meeting for her ideas

- Giving a woman credit for an idea that someone else has spoken as if it were their own

- Providing feedback to women (about her or others that is useful to her) privately when others may have neglected to share such information

- Noticing when people are making unfair or invalidated assumptions (where bias thrives) about what a woman wants or is capable of and instead of letting it go by, simply asking about the assumptions to determine its accuracy

- Refusing to participate in denigrating or unprofessional conversations about women

Career Planning for Women Seeking Leadership Roles

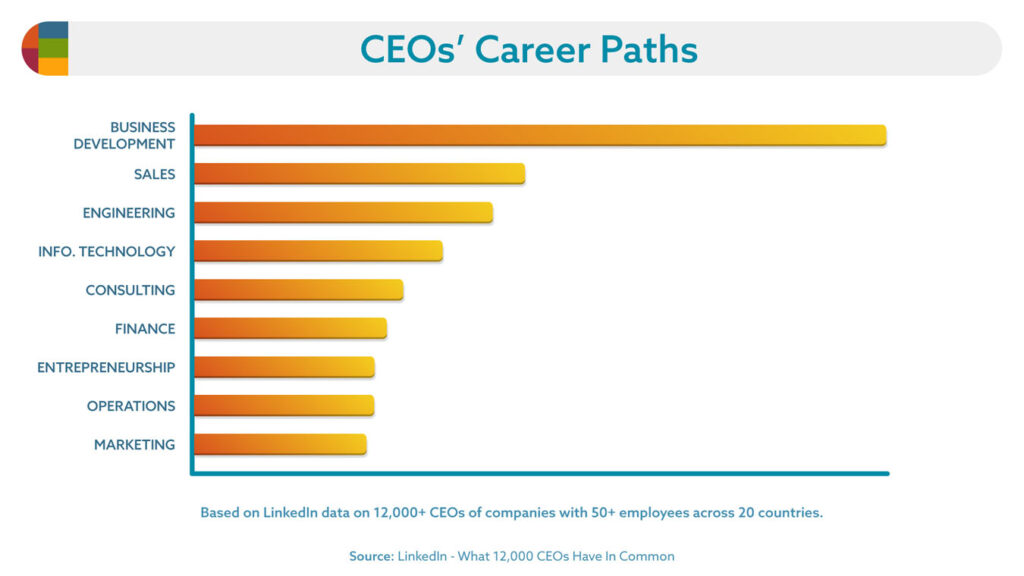

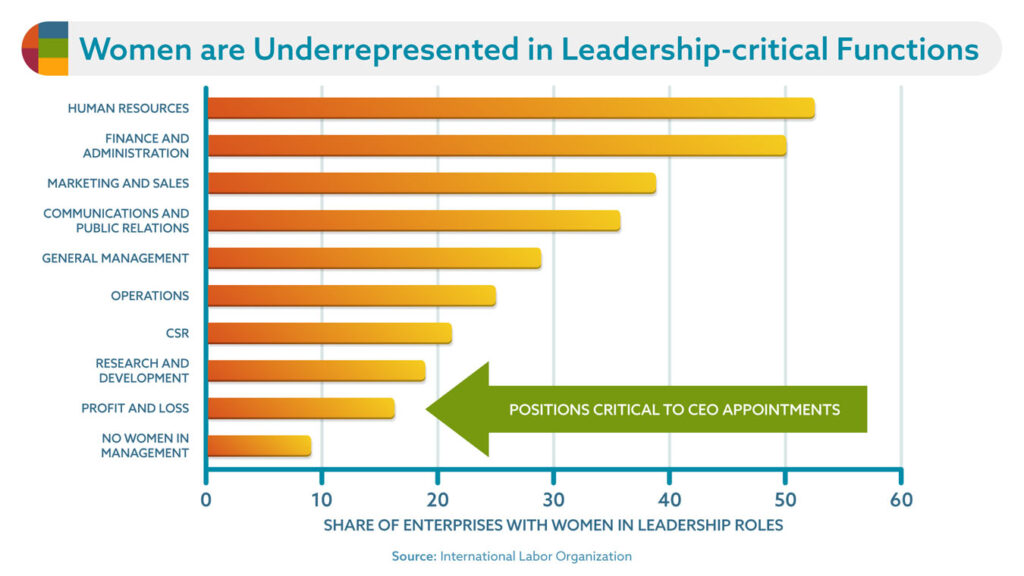

The women who make it past the “broken rung” (where a large percentage leave the leadership track early in their careers) often self-select, and are mentored into, functional areas of responsibility which are associated with the “softer side” of business, such as Marketing, Human Resources and Administration. Statistically few CEOs come from backgrounds in these areas, where women are more likely to gain their core career experiences. In addition, CXOs in these areas tend to be less influential than those with Profit and Loss accountability and experience in “harder disciplines” such as Finance, Sales, Technology, Operations/Distribution and Product.

Thus, women targeting the highest levels of influence and responsibility are advised to specialize in, or gain significant achievements related to, these more highly valued business disciplines. This advice to “do hard” and gain business acumen should be accompanied by mentoring and coaching support to help aspiring female leaders identify where their natural talents and interests are in these areas. It’s also to women’s advantage to understand how their leadership and management successes in a “softer” discipline can help them become strategically and tactically indispensable to the “harder” disciplines they support, thereby increasing their leadership influence and credibility.

Due to cultural and unconscious personal biases, more men than women receive this kind of mentoring support in the normal course of business. Thus, they tend to gain more executive exposure and opportunity for broadening assignments of strategic importance and impact. To counter this unconscious cultural phenomenon, women can become intentional in their career planning to request the kinds of assignments and opportunities that will broaden their practical understanding and specific skills in ensuring that the hard and soft disciplines work together at the strategic level for overall success. Mentors and talent development professionals can also become more intentional in helping women gain such broadening assignments and executive exposure so that those at the highest levels will observe women operating successfully across the “hard” and “soft” disciplines. Such visibility is critical to achieving a meaningful expansion of the top-tier leadership talent pool.

Career-Defining Accomplishments and Future Potential

Regardless of their functional areas of expertise, women who aspire to senior leadership need to achieve significant accomplishments that demonstrate their mastery of both hard and soft skills and their ability to make meaningful and indispensable contributions to organizational success. While strong candidates for any position will have many accomplishments, it’s important for women targeting senior leadership to have a few accomplishments that stand out due to their greater impact. Those accomplishments with the highest impact create a pattern of success that women, their supporters and sponsors can use to tell the story of their past success and paint a picture of their future potential.

Such career-defining accomplishments have three components that demonstrate:

- Mastery of hard skills such as revenue generation, expense reduction, business modeling, financial acumen, risk management, customer and employee retention as well as market knowledge, strategic and global awareness

- Mastery of soft skills, also known as emotional intelligence, such as empowering others, goal setting and management, change management, negotiation, thought leadership, inclusive leadership and influential and consensus-building communication style

- Delivery of quantifiable business impact, in both areas above, and in areas specific to their work, quantifiable proof that the business under their watch improved and exceeded expectations

Several studies point to an interesting dichotomy in how men and women’s talent is assessed: men are assessed based on their future potential, while women are assessed based on past accomplishments. This is true for candidates being hired for leadership positions, as well receiving internal promotions. To meaningfully help women rise to their leadership potential, they and their sponsors must focus on their potential and, as is done with men more readily, use past success and accomplishments as proof of why an organization should give them greater leadership responsibility and opportunity to realize that potential.

Women who focus on their own potential, learning to speak about it with confidence and conviction, help others envision them succeeding at higher levels.

Executive Mindset

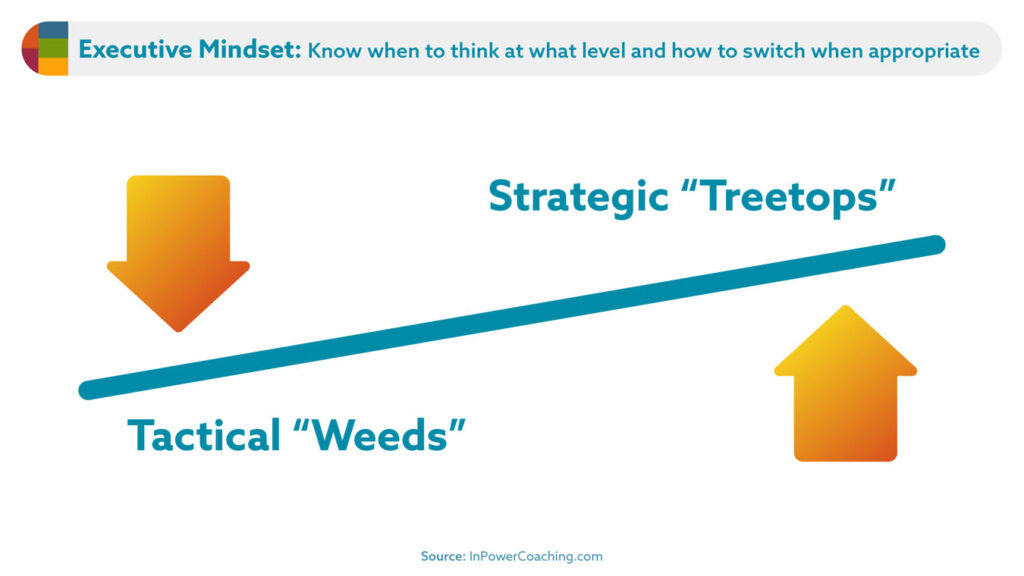

Anyone targeting the highest levels of leadership and influence must move beyond the basic threshold of business acumen into an “executive mindset.” This mindset includes the ability to think and act strategically, with a well-developed understanding of how the entire business succeeds rather than simply understanding the dynamics of one’s own discipline. It requires the ability to get above the details of a particular situation and see those details in the larger and more strategic context. While this is an exercise in learning to understand and operate both in the weeds of specific types of problems, and in the treetops of how issues come together strategically to create opportunities and threats, the ability to switch effectively between these perspectives and operate effectively in both is a skill unto itself. It is a skill that someone who has an executive mindset recognizes to help them determine whether a weeds or treetop view is appropriate in any particular situation.

In addition to this higher-level perspective, effective executives are also champions of their businesses, exuding confidence to stakeholders when the facts of the situation are more precarious. By championing the possibilities and positive aspects of the business reality, executives help employees, customers and others stay committed to helping the business survive hard times and find solutions to intractable problems.

Many women struggle to understand and cultivate an executive mindset because they are not effectively mentored or coached into it, particularly by other senior women who did not receive such mentoring. Men, on the other hand, through role modeling, informal mentoring and more direct development through broadening assignments, are more likely to be supported in developing their executive mindset by other male leaders.

In fact, many women are mentored and coached early in their career towards behaviors and mindsets that are the exact opposite of the executive mindset. They are rewarded for getting the details right, and they are penalized for taking strategic risks and claiming responsibility for their own successes in ways many men are not. Women are told they must work twice as hard as men and that their hard work will be recognized and rewarded. Thus, most women believe that their success will result from hard work, an attention to detail and extreme humility. Unfortunately, these are not characteristics, by themselves, that describe successful executives who can break away from the details to see strategic possibility, manage their workload in realistic comparison to their priorities and demonstrate confidence amidst risk.

Mentors and allies who wish to help women develop their executive mindset are advised to help them earlier in their career to:

- Learn how cultivating both a “weeds” and “treetops” level perspective can help them lead and manage better

- Manage their workload realistically against true business priorities

- Balance humility with a healthy ability to self-advocate

- View confidence as a skill helpful in motivating others and mitigating risk

Thought Leadership for Influence and Visibility

While executive sponsors often spot talent based on good business results, they also pay attention to those leaders who influence other leaders with good ideas. Even so, every woman in business frequently experiences having their ideas ignored, only to be taken up a few moments later and presented by a man as though it was his own. When this happens consistently, which it does in most business cultures, women come to believe their ideas have less value, because the ideas originate from them. This is demotivating for women and unconsciously discourages them from speaking up and valuing their own ideas.

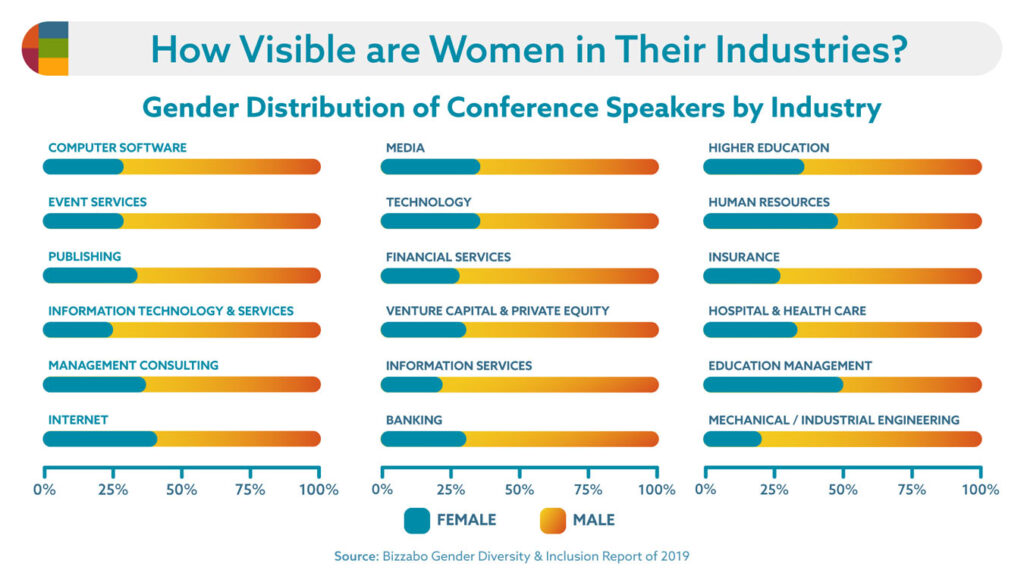

Mentoring women into leading with their ideas is good for the women, good for the business. Moreover, it also gives women greater access to discussions and forums where ideas brew and leaders with potential get noticed. This is especially true at conferences, retreats and executive roundtables, both public and private. It should come as no surprise that the majority of virtually every conference speaker’s list will be made up by men. This is a result of both unconscious bias and women self-selecting out of discussions where the impact of their ideas will gain visibility.

By contrast, when a woman learns to believe in the value of her ideas, to invest herself in developing them and standing for them, she can become influential and gain visibility. Even more powerful, she can shape her ideas, the way she advocates for them and the audience to whom she speaks to help her achieve an intentional personal brand and become known for her potential to lead through the power of ideas. Mentors and allies hoping to support and help women tap their potential for thought leadership can start by:

- Asking women for their ideas and listening sincerely to their responses

- Telling women what they find appealing about the idea(s) they’ve pitched

- Challenging women’s ideas for the purpose of helping them develop them (rather than “winning” with a better idea)

- Giving women credit for their good ideas and sharing specifically how those ideas advance the discussion

- Suggesting to others that they talk to specific women whose ideas could be helpful and facilitating these connections

Such simple measures help women value their own ideas and understand the ways their ideas contribute to the business, while also giving women visibility in the flow of ideas.

Office Politics and Group Dynamics

Many professional women—especially early in their careers—will share discomfort and disdain for “office politics,” an informal term for the way human and group dynamics play out in specific business cultures. Of course, women, being human, are generally as adept and capable of navigating a business culture as any human being, unless the written and unwritten rules of that particular office have been developed in ways that help men succeed more than women. In fact, business cultures which have been founded and developed by women often make their male employees uncomfortable for the same reasons. However, since the broader business culture has been unconsciously developed by and for men over multiple centuries, it is more likely that a woman finds herself in a business culture which has evolved in ways more likely to make her success harder to achieve than a man in the next cube over.

Regardless of the specifics of any particular culture, it’s rare that a leader emerges who is not aware of, and skillful at, understanding and working within the organizational culture to achieve personal and business success. Thus, for a woman to be successful rising into higher levels of leadership, she must come to accept that learning to navigate the business culture successfully is part of her work. She must learn to reframe the “politics” from a game where the deck is stacked against her to view it as simply the particular flavor of group dynamics where she works.

Mentors and allies can help women make this shift in thinking by helping them see the dynamics around them as clearly as possible and learn to authentically modulate their own behavior for maximum effect. Sharing strategies and tactics to successfully navigate the rich human interactions around them is an invaluable step in any professional woman’s development.

Coaching Advice for Women Seeking Leadership Roles

While mentors provide irreplaceable insight into business cultures and business norms, coaches offer a complimentary ability to help women develop intrapersonal and interpersonal skills to gain the influence and leadership successes they seek. While individual women explore many of the same issues faced by men in individual coaching, women as a group face the challenge to develop their authentic-to-them, feminine approaches to leading others. The next two sections highlight some of the most salient coaching themes virtually any woman in leadership will find helpful.

Find Your Authentic Feminine Leadership Style

Because the larger business culture has been historically designed to help men succeed, as they learn to navigate it many women feel that many of their natural strengths have relatively little value. As a result, many women either try to emulate male leadership styles, which often feels inauthentic and are thus less effective, or they lean into their subject matters expertise at the expense of developing their emotional intelligence. Unfortunately, it is their emotional intelligence skills that often help women gain leadership positions and succeed once there.

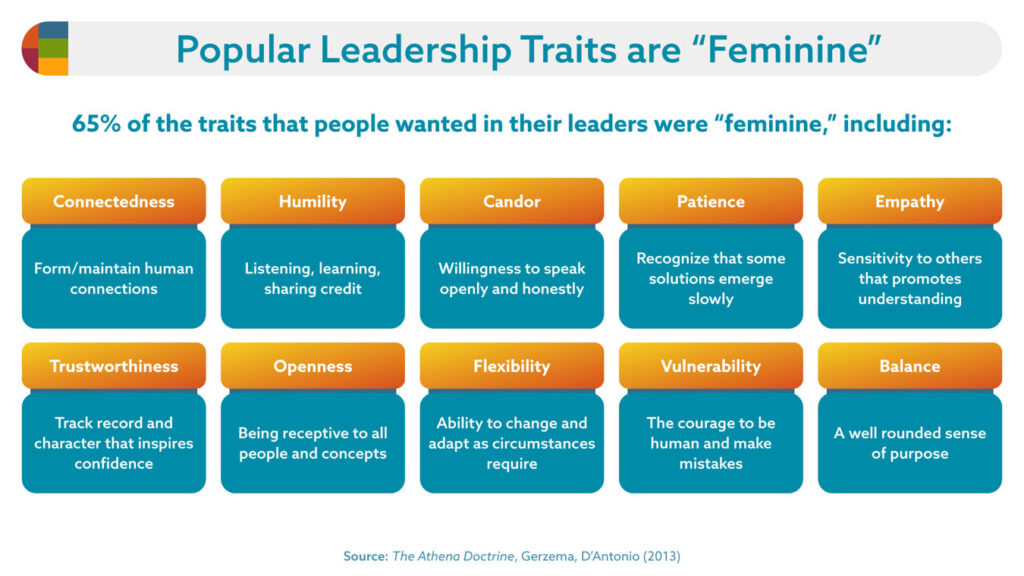

In fact, many of the natural talents women bring to the business world are highly valuable. One global study categorized leadership strengths into those generally viewed as feminine and masculine and, after surveying an international panel, found that 65% of the traits that people wanted in their leaders were generally considered to be “feminine”.

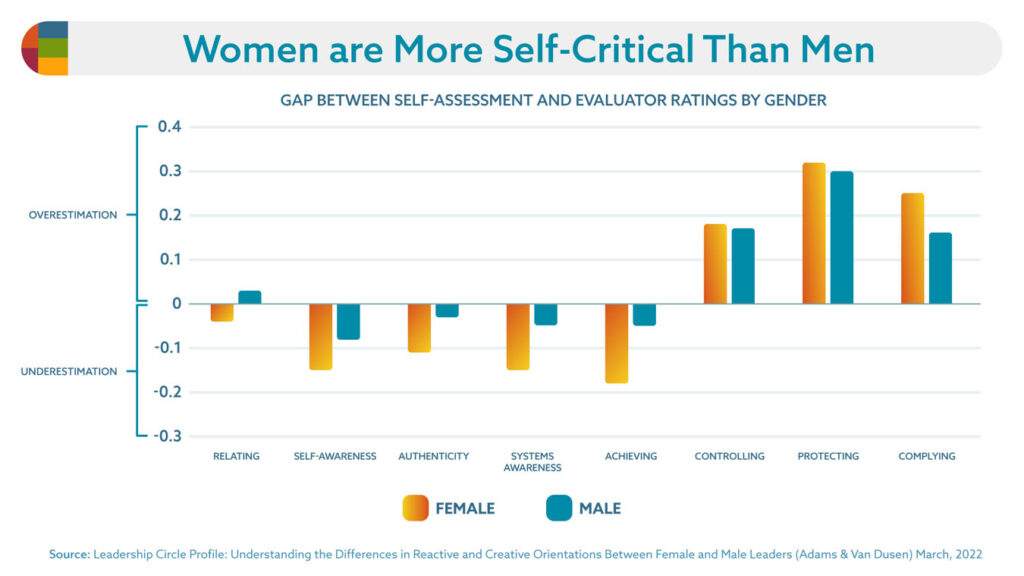

Another study, based on hundreds of thousands of detailed 360 degree assessment results, documented a distinct feminine leadership advantage. Their data shows that, as reported by the men and women they work with, female leaders display greater creative leadership competencies (e.g., systems thinking, relational awareness) and had fewer tendencies to be reactive (e.g., autocratic, arrogance). Specifically, women scored in the higher ranges of leadership effectiveness 8% more often than men, and men scored in the lower ranges 7% more often than women. The researchers noted that these results were consistent with the hypotheses that:

- women are socialized more proactively into leadership-critical relational skills, which men are less likely to be;

- expectations are higher for women so they are harder on themselves and work harder to meet these expectations than their male counterparts; and

- less skilled men may be promoted into leadership more frequently than women.

So, we end up in a strange paradox, in which male leadership characteristics are considered “the norm,” and are rewarded even when effective leadership skills are lacking. This appears to be true even though the traits most often exhibited by women contribute to greater leadership effectiveness and are “most desired” by a majority of respondents when gender identification is removed from their judgement. This is very confusing for many women and exhausting for those who burnout trying to meet excessive standards. Many women are frustrated because they believe that their feminine leadership style is the best way to lead, as is proven by studies like the ones above, yet they are less frequently rewarded for their skills in these areas. They are often told to be tougher (which they interpret as less relational and empathetic) and more like the men, and yet penalized for a lack of femininity when they comply.

A woman who wants to be an effective leader first needs to believe that what she brings to the table—not despite her gender, but because of it—has value and will contribute to the business. And she must learn to believe this even when others tell her both directly and indirectly that the opposite is true. She must also learn to temper her own self-criticism to reduce her exhaustion and find the capacity to push ahead without the same amount of cultural support the men in her workplace may receive.

The simplest way for a woman to value herself is to identify the tangible business results that come about because of her leadership style and take credit for them. In addition, she must learn to identify what she believes is a weakness and to learn to see the ways in which it helps her be effective. For example, many women are told they are too empathetic, so they shut down their emotions, believing that emotions in the workplace are a zero-sum game. In fact, emotional intelligence is a highly prized leadership skill. When women (and men) learn to use their emotions to bring them critical information about a wide variety of situations, they can more easily determine when empathy is exactly the right response to an employee or customer issue, and when a “tough love” approach might be more effective.

To gain this kind of insight, she must also surround herself with people (coaches, mentors and colleagues) who help her see her natural strengths at the same time they challenge her to grow and develop beyond them.

Befriend Your Inner Critic

Even when women learn to internalize their value, they almost universally find that a “little voice of doubt in their head” has internalized the negative voices about themselves (or women in general), which they’ve heard over time. The little voice acts like an inner critic (often a product of psychological gaslighting,) channeling unconscious negative biases, encouraging her to interpret events in ways that accentuate potential negative outcomes and threats. It “reminds” her that playing small, eschewing visibility and accepting inequity can protect her from confrontation, conflict and the possibility of being shamed, hurt—or fired.

If a woman has experienced harassment or abuse related to her gender, in the workplace or in her personal life, her inner critic tends to be even more effective at shutting her down, so she withdraws from situations of discomfort and potential conflict. This means that anyone in her circle who reinforces the negative internal voices causing the shut-down, even those with good intent, also reinforces the after-effects of the abuse.

The inner critic feels like an inner enemy, always sapping her confidence and weakening her spirit.

The little voice is particularly adept at triggering women into unhelpful emotional reactions which, whether they express them or not, increase their stress and cloud their ability to experience common workplace situations less personally and more clearly.

The psychological function of the inner critic is to be helpful, to be protective by drawing a woman’s intuitive awareness to potential threats and providing insights that may avoid negative outcomes. However, if the little voice is shutting down her participation in day-to-day or high visibility discussions, it’s overcompensating and actually harming a woman’s chances of success more than helping her.

The best strategies to combat the little voice of unhelpful criticism are to:

- Learn tools to detrigger and rebalance emotionally by clearing away reactions that are more habitual than related to the actual situation

- Assume the little voice’s positive intent and get into dialog with it by learning to engage in an inner dialog through expressive writing or other means of gaining self-awareness

- Practice the “Silence Trick” of not voicing self-deprecating negative thoughts, which decreases a woman’s standing in the eyes of others

- Learn to “fake it ‘til you make it,” ignoring the little voice for purposes of learning what happens when that voice dictates one’s actions

- Get help from a therapist, coach or mentor to gain perspective on what psychological function the little voice provides and find healthier ways of achieving it

- Get over perfectionism and learn to learn from failure and disappointment

Become a Master of Intention

Many of the dynamics mentioned above—negative unconscious bias, cultural norms that devalue women’s strengths and internal voices of doubt that sap a woman’s confidence, not to mention workaholic and toxic cultures—leave many women feeling stressed and helpless to successfully navigate a way into leadership positions. If she also has demands from her personal life that reinforce these challenges or divide her time and energy to deal with them, even the most talented woman can conclude that the game is rigged and decide that she’ll be happier and more successful if she passes up management roles to pursue success as an individual contributor, or as is increasingly common—entrepreneurship.

The bottom line is that even with good mentors and supportive bosses, to succeed a woman who stays in the organizational game to pursue leadership roles, has to become an expert in managing her own energy and the energy of her teams. She can do this by becoming an expert at setting, and managing to, her intentions.

Since there is never enough time or energy for everything, success becomes a matter of ruthless prioritization and focus. Here again, cultural norms work against women as many of them are acculturated to feel they cannot say “no.” While there are complex dynamics behind the discomfort many women experience when they want to refuse a request for their time and talent—including anxiety about being disliked and an assumption that their own path to success means working twice as hard as the men around her—saying no and establishing effective boundaries are some of the most important skills she can master. Psychologically, she must learn to say no to lower priorities in order to say yes to those that matter.

But how to prioritize the flood of things that demand her time and attention? The key turns out to be an ability—a skill—to define success proactively and so clearly that the activities that must happen for it to be possible are immediately obvious. Often identified as a leader’s ability to articulate a vision that guides the team, expanding the concept to a leadership intention offers women (and men) the ability to identify the success state more holistically and in ways that help individuals and teams manage prioritization as a practical matter.

Become a Master Communicator

Communication is a key factor in any leader’s success, and it is one of the most richly varied topics in psychology, sociology and leadership for good reason. Communication is the fabric of human relations, interpersonally, organizationally and culturally. There are no quick “tips and tricks” for mastering communication, however, there are several common themes women confront and can overcome to become more effective.

Stop voicing powerless thoughts about yourself.

Women are more prone to speak about themselves in negative ways (often in response to their “inner critic”), which shapes people’s experience of them and encourages others to see them in more powerless terms. A common example most people are familiar with is the verbal pattern research has dubbed “double voice discourse,” more commonly understood as “pre-apology.”

A pre-apology happens when someone begins a sentence with a self-deprecating phrase, such as “I know I’m not the expert here…” or “I may be speaking out of turn, but…” or “It’s just a thought, but…” While many women say things like this unconsciously and frequently, the emotional function of such speech patterns is to lower other’s expectations about what they are going to say before they say it. It signals to everyone present that their ideas probably have reduced value. The simple solution to shifting this unconscious habit is for women to learn to hear when they say these things, or other things that effectively diminish their value, and then not to verbalize them. This “silence trick” goes a long way towards helping a woman communicate more powerfully and clearly. However, it often brings up uncomfortable feelings in the women themselves, taking away this protective habit can make them feel more vulnerable. Many women defend this habit by saying they don’t want to raise expectations, increasing their likelihood of failure and shame. The solution is not to continue the habit, but to reshape it in ways that reduce feelings of vulnerability by choosing to only say things they believe in and are willing to stand behind and choosing silence in between.

Take People at Face Value and Say What You Mean.

When the little voice of doubt in her head during a conversation becomes unhelpfully loud, a woman easily second-guesses herself about what she’s hearing, what she’s feeling and what an appropriate response may be. This is particularly true for women earlier in their career and it leads many women to hold back from putting their ideas out there in strong ways, or even speaking up at all.

While it’s true that everyone she interacts with will not necessarily have her best interests in mind, a woman seeking to cut through her internal chatter to become an effective communicator takes a strong step forward by simply letting go of her internal dialog, believing that others mean what they say and choosing to speak up for her ideas. For many women this feels frighteningly risky, yet it is the crucible through which they must pass to put themselves into more powerful dialogs and learn more nuanced ways of championing their ideas.

Learn to be authentically positive.

Many women are very talented at intuiting and analyzing long-term impacts of short-term actions. They are skilled at evaluating risk (see below) and seeing the downsides of short-term thinking. While this is a skill all businesses need, it is not necessarily a skill all business leaders value. In particular, while women can become acculturated to focusing on risk and negativity, many men are acculturated into a greater sense of self-confidence, which leads to an overdeveloped sense of positivity.

The communication dynamic this often sets up in a workplace context is that many women come to feel responsible for being the “voice of reason” at the table and reminding people of all the possible downsides to their plans and actions. A woman who takes on this role runs the risk of being labeled the “Negative Nelly” or “Debbie Downer.” Besides being unflattering, more importantly this kind of reputation is the exact opposite of the leadership style desired in powerful leaders who exhibit an executive mindset which include the ability to build confidence in teams and help people believe that the business can pull out of challenging situations. The solution is for women to learn to speak with positivity, while also recognizing and speaking about negative realities and possibilities. It is a learned skill, and one highly effective in leadership circles.

Become a Master Risk Taker

It is commonly believed that women do not like risk. This unfounded belief about women in the professional setting is often cited as a reason for not “taking a chance” on them for leadership roles, which generally require a tolerance for managing risk and uncertainty.

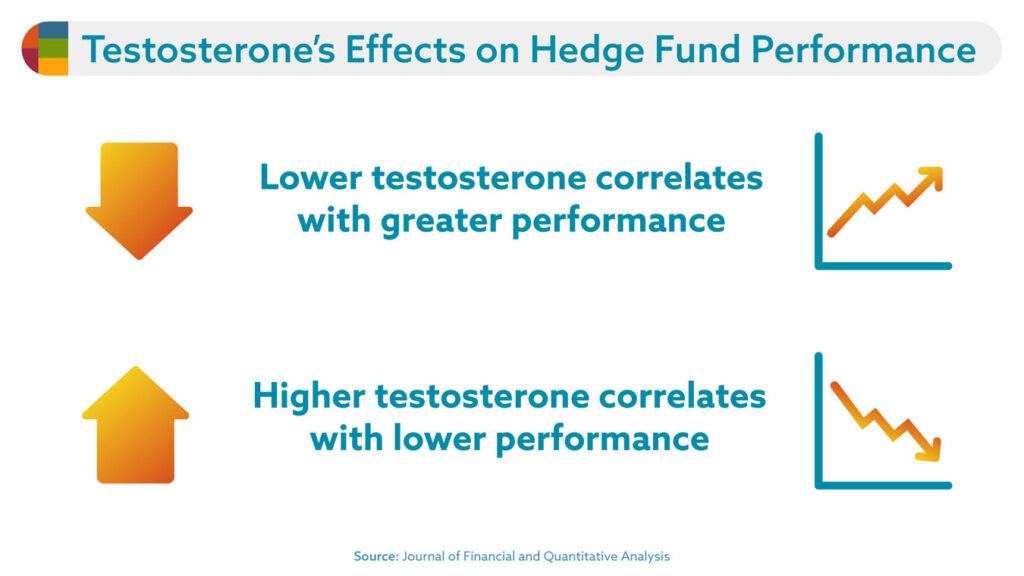

It’s also ironic because women are, in fact, no more or less effective risk takers than men, and often succeed in producing business results because of their good judgement in evaluating risk. One distinction that sets women apart from their male colleagues is that rather than taking unfounded risks, women are often more apt to do more research before placing a bet in decision-making, and they are more likely to mitigate risk by seeking incremental, and consistent, reward. Given the role of testosterone in risk-taking behavior, women appear to be better “considered risk takers” than many male leaders who have been acculturated into taking unfounded risks to demonstrate confidence and land huge rewards. As a result, it’s common for women and men on teams to overcompensate for each other’s “tortoise and hare” approaches to risk. There is obviously a role for both: researching risk to go in eyes-open and learning to play the high-risk-high-reward game that often leads to business success.

Both female and male leaders benefit from mastering the game of risk that defines business success. However, the dominant business culture tends to reward men who have built a personal brand championing big, “bold” risks more than it does women who “keep their head down” and take smaller, “safer” risks. A woman who seeks higher levels of leadership, especially the executive suite and board appointments where every decision involves risk, must counter the tendency to be painted as someone who only takes safe risks and is uncomfortable being audacious. They must find a comfort level with risk that balances daring and considered risk. They must also take enough bold risks that pay off through their career so they can prove to those who want to take a risk on them that they are worth the bet.

Become a Master of Situationally Appropriate Leadership

Talking about “leadership style” grammatically implies that leaders respond to every situation the same way. In fact, the most effective leaders are those who evaluate each situation uniquely and craft their response for maximum impact. This means, for example, developing one’s ability to be decisive when immediate decisions are necessary, and collaborative when time allows for it and engagement is imperative. It means, for example, managing Sue with “tough love” and Joe with empathy if they need different kinds of motivation and a specific circumstance. It means understanding what each kind of success calls for and becoming skilled at responding in ways that conform to both “masculine” and “feminine” norms as each situation demands.

In fact, this isn’t just a requirement for women, it’s equally important for men to master a full spectrum of leadership styles and responses to achieve leadership success. However, when women master the skills of versatile and responsive leadership styles they can actually reap rewards greater than the men around them, benefiting in both promotions and salary.

Strive for Work-Life Equity instead of Work-Life Balance

Much has been written about the struggles working women (and especially working mothers) have with work-life balance, and for good reason. Particularly in American households, married women spend nearly twice as much time on household and child-related tasks as their husbands. Finding effective ways to meet the demands of a professional life and a personal life is a challenge every working person juggles. However, the higher in leadership anyone goes, the more often it becomes a requirement of the job for one’s professional demands to take higher priority than personal ones. Sometimes this is a result of unhealthy, workaholic business cultures, but it’s just as often a reality of executive leadership roles, because the most significant business problems tend to roll uphill, escalating to more and more senior leaders, seeking someone with the authority to fix them. By the time they get “to the top,” they are often at the critical stage and truly require attention so as not to put the business itself at risk. These five-alarm-fire business problems do, then, tend to overshadow all other priorities (business and personal) by the time they land on an executive’s desk.

While men find this work-life imbalance a challenge to navigate just as women do, it’s a much less likely scenario. Women more often struggle with work-life balance because they, their colleagues and families, have acculturated to the assumption that the woman is the default fixer of personal challenges while men are the default fixers of business challenges. A woman aspiring to a leadership role trying to become a leader, then, is usually trying to be seen as a reliable fixer of business challenges while also meeting her own (and others’) expectations that she will be the reliable, default fixer of personal issues as well. This problem haunts single and married women, mothers and non-mothers alike.

Even though men and women both wrestle with work-life balance issues, it’s a disservice to everyone to frame it as a uniquely female problem. In fact, the typical work-life balance dialog obfuscates the fact that juggling personal and professional demands is both an organizational challenge to retain productive and capable employees (of all genders and family statuses) and a familial challenge that all genders must manage at home. The truth is that for many families, managing a healthy home situation and rising into the executive ranks don’t always mix. Women are often expected to carry more of the burden at home, leaving them less time and energy to take on more responsibility at work, which is probably why female CEOs divorce more often than male CEOs so that they can stay on the leadership track. Those women in higher leadership role whose families stay together often have supportive partners and other forms of “backup” at home. It’s also true that businesses that burn out their employees with unrealistic, toxic-to-personal-life and workaholic cultures pay high costs in employee turnover and disengagement.

And despite 82% of working parents claiming that company-provided childcare benefits are meaningful employment incentives, only 6% of U.S. companies actually offer them.

For women in leadership, the task to address these issues is double.

- First, women themselves must negotiate equity in their personal and professional lives and partnerships so they can be available to handle the five-alarm-fires at work even as they meet their personal obligations in accordance with their values.

- Second, as they rise into leadership, female leaders must leverage their personal credibility and familiarity with the problems of “work-life balance” to become organizational champions of work cultures that allow all employees (i.e., women, men, parents and caretakers) a chance at “work-life equity.” This increases everyone’s chances of being successful at home and in the office. In particular women must help destigmatize the unconscious-bias-informed-notions that productivity is a function of time in an office chair, that men who tend to the demands at home are weak and that women who protect their time with their families cannot be effective leaders.

How to Craft an Authentic Executive Presence and Personal Brand

This is not an airy-fairy truth, it’s a fact that the higher in an organization one leads the more impactful their decisions and the more uncertainty surrounds them. A leader who does not inspire confidence amid uncertainty is ineffective at helping the team find their way through it. For this reason, executive teams and boards seek leaders for the highest posts who have a history of business-saving accomplishments and who exude the kind of confidence that help others believe success on the path forward. To be put in the ever-shrinking pool for these top leadership positions, a rising leader must have a reputation that speaks for their potential to achieve through risk and inspire confidence in others.

Be Who You Are and Why

The best leaders are known for their authenticity and straightforward ways of dealing with others, which breeds trust and respect between people even in the tension of disagreement. Such authenticity occurs when the leader owns their strengths and their perceived weaknesses, working to leverage both where possible, and mitigate any risks that inevitably come along for the ride. Where women often struggle to trust their authentic strengths, and own their weaknesses, is where their personal brands can begin to work against them in the quest for leadership.

Though it’s often unconscious, when women are inauthentic—trying to lead like a man instead of owning their feminine leadership style or downplaying their business ideas—women can telegraph a subtle sense of inauthenticity, a sense that what you see is not what you get. Alternatively, if she is uncomfortable with her own ability to lead, a woman may display a sense of defensiveness that unconsciously implies she has something to hide. Regardless of the source, inauthenticity leads to a lack of trust in others and an exhaustion for the woman herself who is working twice as hard to keep parts of herself hidden. By contrast, women who own their strengths and weaknesses, and grow beyond them to deliver meaningful results with confidence, can gain the trust and visibility others need to see to take a chance on putting them into the highest roles. For the many reasons above, being themselves can make women feel vulnerable and uncertain, yet when they tap into their strong sense of “why” they find the strength and courage to persevere. Finding a strong sense of purpose is often the key to pushing forward, trying new things, and changing for the better to become capable of achieving great things.

Take on Conflict, Competition and Negotiation

Just as many women are uncomfortable with office politics because it feels like a game rigged to ensure their loss, many women also feel uncomfortable in situations full of competition and conflict. Unfortunately for them, business is a competitive game and people don’t always agree. In fact, successful leaders at all levels spend the majority of their time trying to contribute to competitive advantage and make decisions between competing options and points of view. This means that mastering the ability to take on conflict and competition is a mission-critical skill for men and women hoping to climb the corporate ladder into higher levels of leadership.

Many women can learn to play the business game (like any man would) on the sports field, which gives some women a slight advantage if they’ve played competitive sports. However, for many women (even if they have trophies on their wall), straight out competition that produces winners and losers through head-to-head fights in an office context, goes against their values and their style. Feminine leadership styles typically emphasize collaboration, empathy, and consensus. When women try to lead this way in highly competitive environments, their peers and superiors quickly communicate a lack of faith in their ability to “cut it,” which often undermines their confidence in themselves, starting a negative spiral in their confidence. Often in these situations, women leaders choose to leave rather than play a game that feels inauthentic and mean-spirited to them.

While it is important for everyone to work in business cultures that align to their values and strengths, it’s also important for rising leaders to find wins in every kind of environment before they move on. By sticking with it in a tough environment, female leaders build their skills for future situations where competition and conflict are present, and it expands their career story of mission-critical accomplishments.

One key to a woman’s success in a competitive environment, where traditionally feminine leadership styles go unrewarded, is often to become a skilled negotiator, seeking outcomes that are “win-win” with a communication style that is “both/and.” Negotiation tends to be a more relationship-oriented way of addressing conflict than outright combat, allowing women to lean into their people skills. In direct negotiation, as with day-to-day communication, a woman can also help teams and colleagues expand their view of possibilities by countering the “either/or” mindset that tends to flourish in competitive environments by identifying ways both “sides” can succeed, switching statements from “do we do A or B?” to “how can we achieve both the outcomes A and B could produce?”

Many women, especially early in their career, feel uncomfortable when they have to negotiate, because they have anxiety about “losing.” Yet learning the crucial business skill of negotiation brings other benefits along with it, including learning not to take business dealings so personally, becoming comfortable with risk and turning conflict into a way forward.

At the end of the day, any woman who hopes to rise in leadership must learn authentic ways of managing competition and conflict to produce meaningful business results. Becoming known for doing this well becomes a critical piece of her personal brand.

Make Friends with the Imposter Syndrome

Many women struggle with the “Imposter Syndrome” as they climb higher in leadership. The Imposter Syndrome is a mindset of vulnerability that descends on a person when they feel that others think more highly of them than is warranted. Specifically, it is the fear and anxiety of being “found out,” for the “fake that I am” and then being shamed and labeled. Often delivered by their inner critic the Imposter Syndrome can give the most capable and confident leader everything from butterflies in her stomach to panic attacks. Early in their careers, many women feel confident because they’ve gained the advantage of strong mentors and are enjoying the successes and rewards of their work. It’s not until they are on the brink of high-level leadership roles that they encounter this self-defeating way of thinking. At the point where they will have fewer mentors, greater visibility, greater influence and “more to lose,” the Imposter Voice of their inner critic becomes very loud, sapping their confidence, encouraging them to play small, quiet their voice and—worst of all—shy away from risk, conflict, and competition. Following the Imposter’s (mis)guidance is sure to stall any woman’s climb on the leadership ladder, adding insecurity to her personal brand reputation and giving others reasons not to have confidence in her ability to make tough decisions and manage through uncertainty.

Men also experience the Imposter Syndrome, as do under-represented minority leaders. It’s a common human phenomenon when we’re in our stretch zone, uncertain about how to succeed doing things we’ve never done before, or in environments and situations we’ve never encountered. The Imposter is particularly prevalent in higher leadership for both men and women because there are fewer people who can tell you how to succeed, fewer mentors and coaches who’ve been in the leader’s exact shoes. It just so happens that most men have been given a Voice of Confidence in their heads that many women have not been acculturated with.

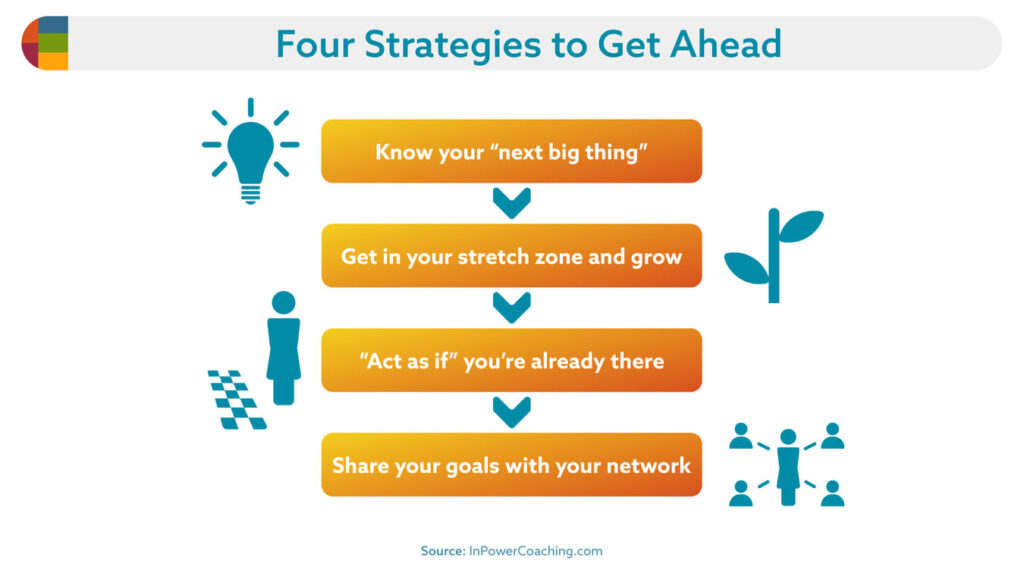

Women seeking leadership positions, without a strong inner voice of confidence, must build their own strategies to counter the Imposter within. For starters, as they do with their inner critic, they can befriend it, letting it point them at areas they need to strengthen and insecurities they need to grow beyond. They can also leverage strategies to help them become more comfortable in their stretch zone such as:

- Setting specific stretch goals to build their confidence one skill at a time

- Acting “as if” they’d already succeeded to bring their intuition and “gut” reactions to help them navigate uncertain and uncomfortable situations

- Leaning into the fears to dispel them, asking themselves questions like “what would I do if the worst actually happened?” And “what would I do if I were not afraid?”

Take Credit and Ask for What You Want

While humility is an important leadership trait, too many women in leadership take it too far, to the point where their colleagues and potential executive sponsors don’t know enough about their successes to champion them for the kind of opportunities they hope to find. This dynamic is particularly problematic when the women themselves are competing for leadership positions alongside men who feel no compunction about talking about their success and putting bold goals out there to their mentors and sponsors.

Too often, women have an unfounded expectation that if they put their head down and don’t talk about their accomplishments and goals, their good work and results will be recognized and rewarded with an offer to do exactly what they want. It’s as if they unconsciously buy into the myth of Cinderella, that recognition and opportunity will find them even if close their eyes and wait. And of course, sometimes, especially early in their career when organizations are seeking out talent to develop, this can be true.

However, often in higher levels of leadership where competition is fierce the opposite is true. Unless women speak up about what they want, and help others see the reasons they deserve a shot at it, others will be sure to step into the void to promote themselves. The woman who is too quiet about her goals and results will never be noticed at all.

Influence by Speaking So They Listen

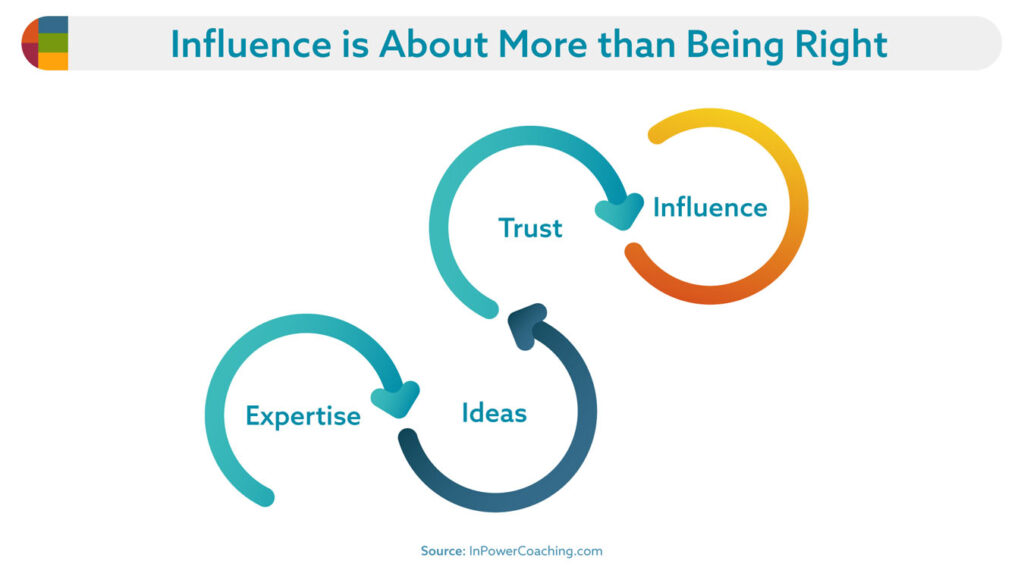

No leader makes all the decisions and takes all the actions that lead a business to success, which is why the best leaders are skilled at influencing those around them and in positions of authority. The ability to influence others is a fine art, which combines an ability to:

- Build trust

- Leverage others’ motivations

- Introduce useful ideas at the right time in the right way

- Physically moderate their voice and presence in ways that contribute to their credibility

Note that “knowing everything there is to know” about a topic is not on the list above. Expertise and facts only go so far in influencing others. Due to unconscious bias factors such as confirmation bias, negativity bias and simple human dynamics, influence is more an emotional intelligence skill than a straight-out cognitive intelligence skill.

Yet, many women in leadership feel that until they have all the facts and answers to all the questions they could possibly be asked, they won’t speak up and try to influence important decisions. This lack of confidence holds them back from situations where they can gain visibility, credibility and influence. While not every opportunity to influence big decisions is a risk worth taking, shying away from many of them builds a personal brand of shyness and uncertainty that tends to work against their efforts to be given a shot at higher leadership opportunities.

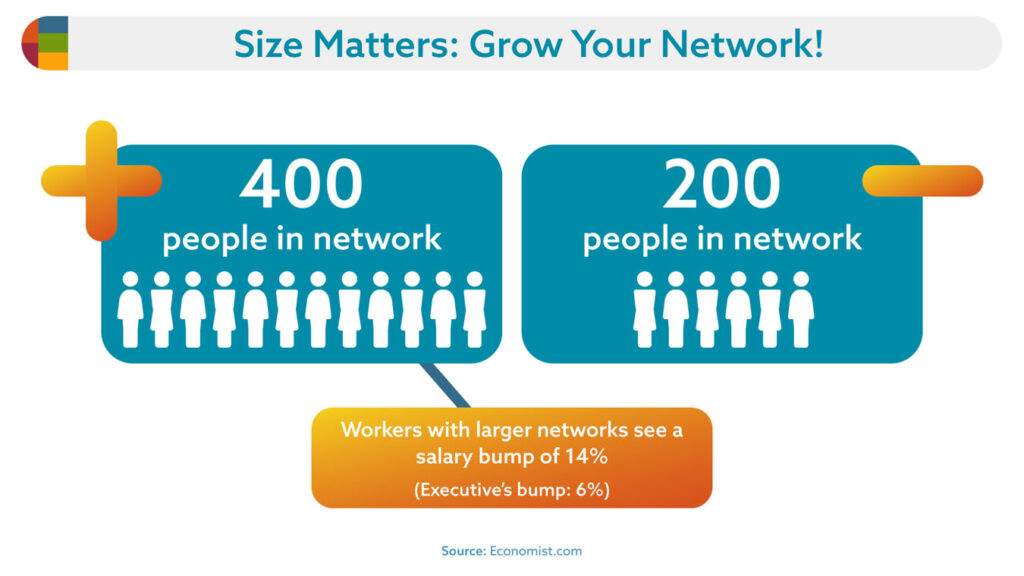

Network Authentically and Strategically