Mentoring Women Key Takeaways:

- Mentorship Must Evolve: Traditional mentoring advice often perpetuates outdated gender tropes that hinder women’s leadership potential. Mentors need to update their guidance to reflect current workplace realities.

- Unconscious Bias is Pervasive: Mentors can inadvertently pass on biases to their mentees, limiting women’s progress. Recognizing and addressing these biases is crucial for effective mentorship.

- “Truths” Have Become Tropes: Many common workplace truisms about women, such as needing to work twice as hard or avoiding emotional expression, are now harmful stereotypes.

- Imposter Syndrome is a Crucible: Women shouldn’t internalize imposter syndrome as a flaw but view it as a growth opportunity. Mentors can help them reframe this experience.

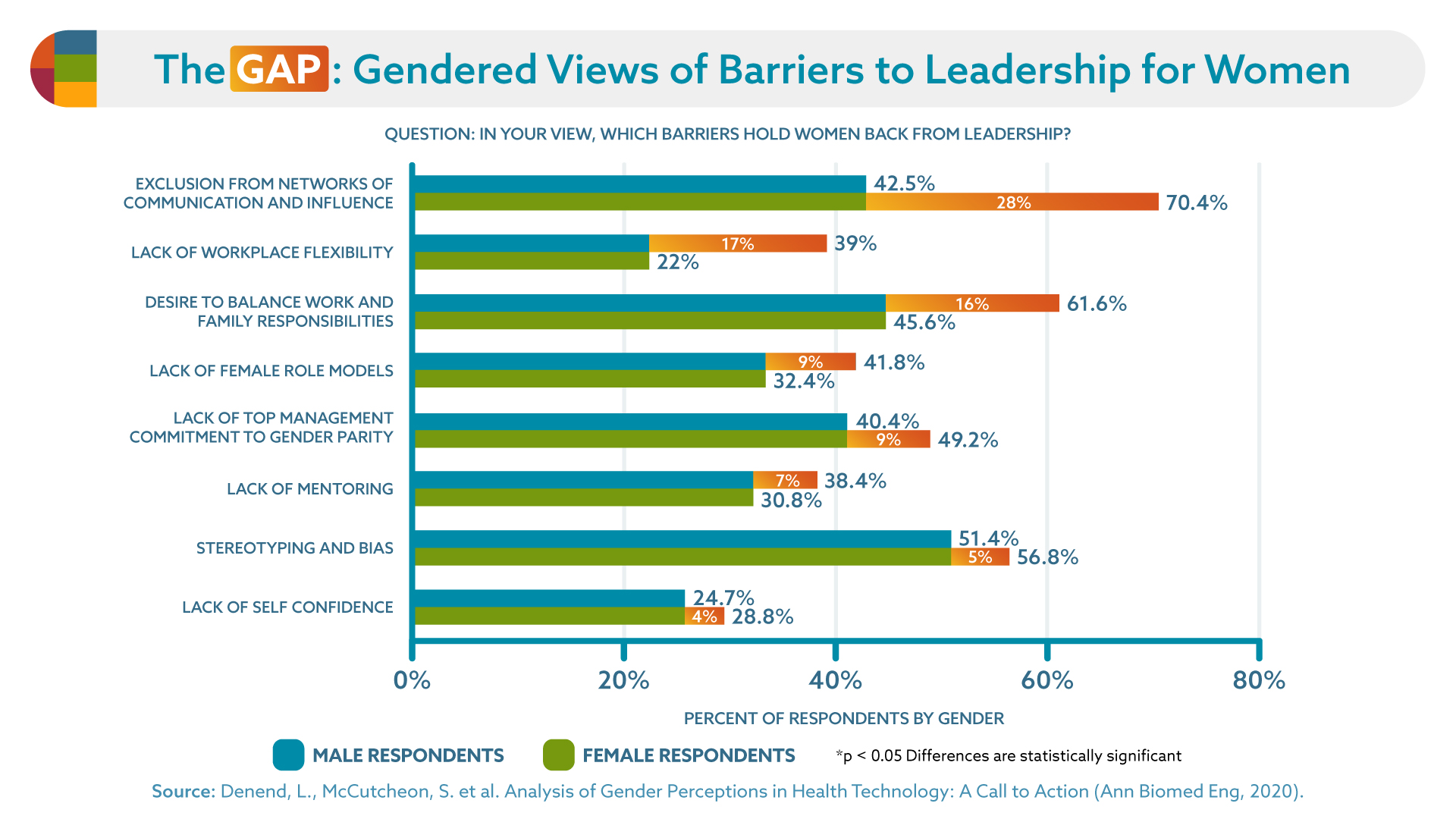

- Women Face Unique Challenges: Women often navigate systemic biases and pressures that impact their careers. Mentors must be sensitive to these issues, even when they are outside their own experiences (a good opportunity to learn!)

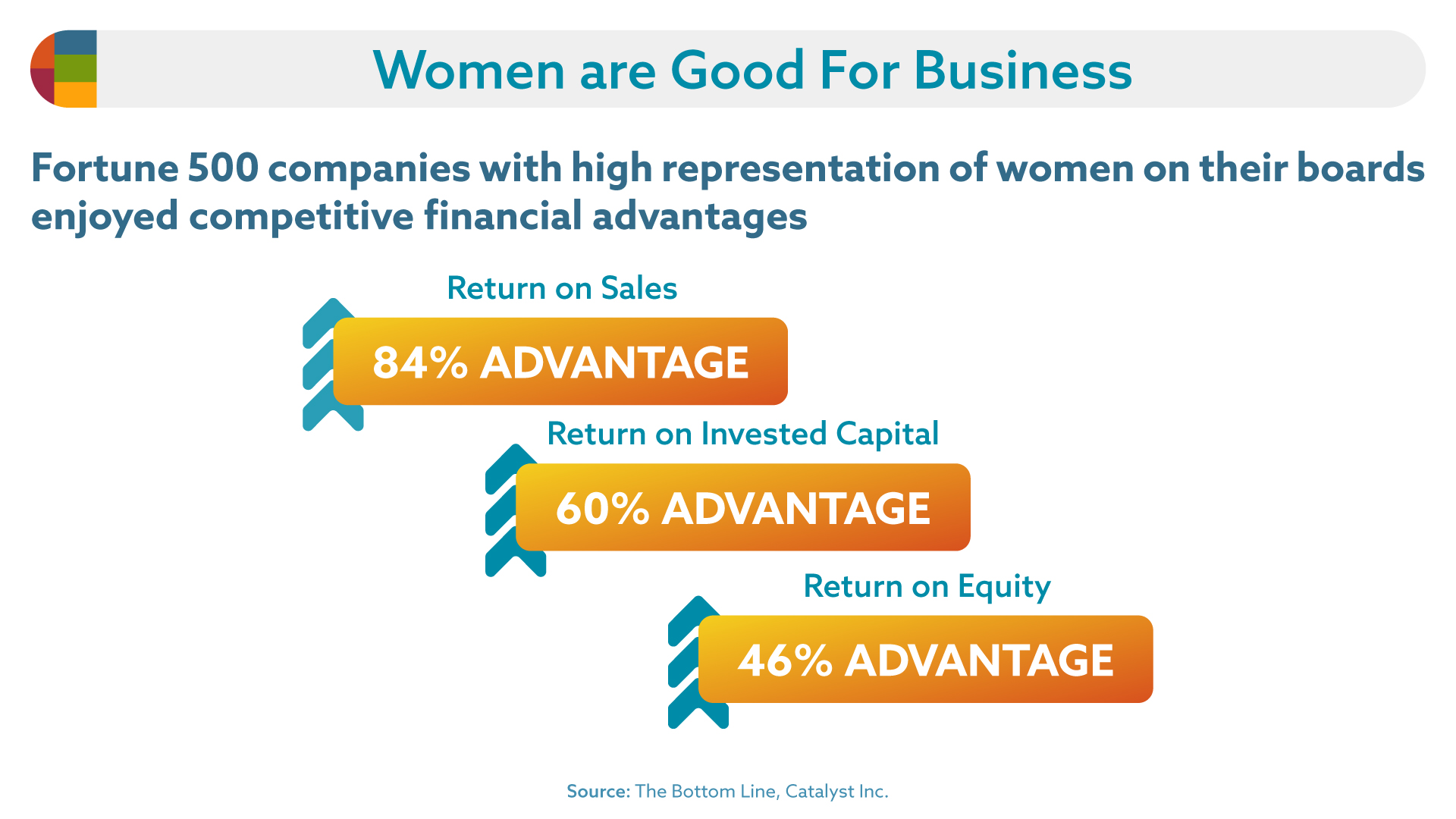

Women are good for business.

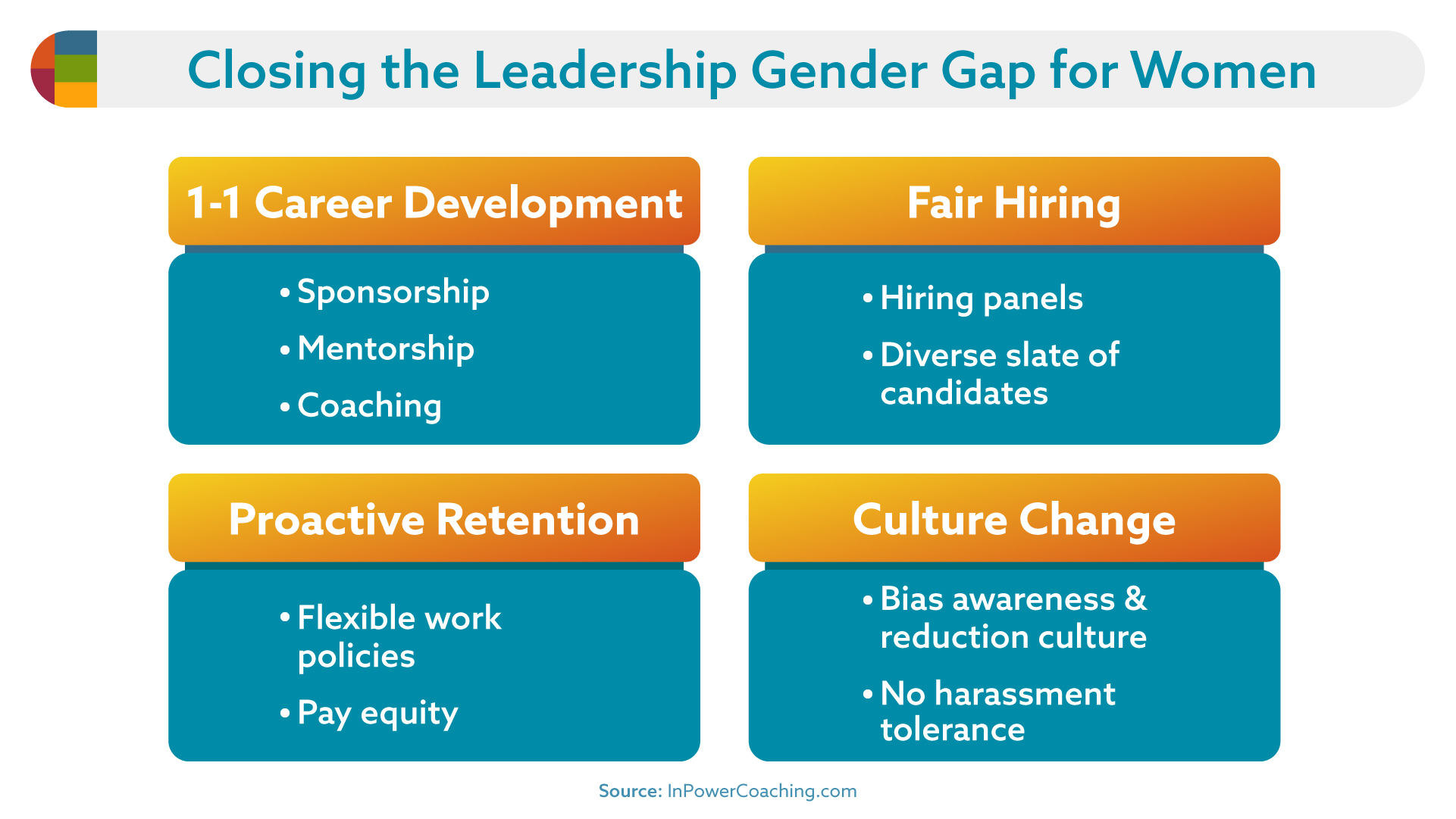

For decades women and their mentors have worked together to solve the puzzle of how to raise more deserving female leaders into leadership positions in all kinds of organizations. This focus on programs for mentoring women has contributed to great progress elevating women into leadership, but there is still a long way to go in facilitating effective mentorship and sponsorship of high-potential women.

After experiencing a number of organizations and workplace cultures myself as a leader, and coaching other women on the leadership track for almost a decade, I’ve come to the conclusion that too often mentoring simply passes down experience from previous generations, from all genders. Unintentionally this process essentially bakes in some of the barriers the mentors faced in earning their way into senior positions. I believe that to change the cultures that create barriers for advancing women, mentors and mentees together must level up their collaborations and better navigate biases to women’s workplace progress.

Women and the champions hoping to help them must put away outdated tropes about leading while female, taking on new truths that better empower them in today’s workplace environment.

Without this work to adapt mentoring advice to today’s workplace realities, people presenting as feminine are left deserving of better mentoring than they often receive. And the best part is that when female and male mentors take on such proactive collaborations with their proteges, they help more female leaders and become better leaders themselves–to everyone.

Mentoring Women – Today

Mentoring women requires more than just sharing your own experiences, regardless of your gender. This is because times, tropes and gender truths have changed since most mentors have been in the trenches their proteges work in today. To provide effective guidance to support women and gender equality more broadly, they need to update their understanding of the workplace realities women experience in light of new research and social dynamics. Specifically, recent research has a lot to teach us all about the role of unconscious bias in perpetuating unfair and discriminatory workplace cultures, including through mentoring.

The more research teaches us about bias and the way it burrows itself into our workplace cultures, the clearer it becomes that our mentors have their biases, too. And unless a mentor learns to see around and through their own biases–especially those related to gender in the workplace–the more likely they will simply pass them on to their proteges. This self-perpetuating bias dynamic–while natural–does a great disservice to both mentors and mentees, denying the protege empowering insights into how to overcome unconscious discrimination. It also cheats the mentor of new opportunities to expand her or his professional mindset. This is true for women and men who see gender dynamics differently) offering individual practical advice and/or participating in a mentoring program.

While each individual has their own challenges and experiences built out of their personal relationships and cultural context, there are some common workplace bits of mentoring advice for women that desperately need updating to factor in the impact of bias, recent research data and current values and social norms. This out-of-date advice perpetuates the gender gap and is based on workplace truisms born out of the 1970’s when women were relatively new to any kind of leadership. Almost 50 years later, what were once truths have become tropes.

Whatever “truths” you faced earlier in your own career have evolved. When you set out to mentor a woman today, whether individually or through a mentorship program, it’s time to update yourself on the new truths you should be passing on to them.

Make no mistake, most of this advice still has truth in it, for women and often for under-represented leaders more broadly. But times have changed and when mentors pass it on in its original form it is actually doing more to hold women back than to help them succeed authentically in today’s workplace culture.

Here are the much-needed updates to truths that have become tropes. Use this guide to ensure that the advice you give female up-and-comers does not integrate outdated biases and stereotypes now proven to hold women back.

Download a 1 page PDF summary of these tips.

TROPE: You must work twice as hard for half the credit.

Thanks to confirmation bias, a boss who expects a woman to underperform will be more likely to undervalue her contribution, effectively raising expectations for her performance in comparison to her male peers. This truth requires women fighting unfairly high expectations in their superiors and peers to over perform without extra compensation in order to be seen as competent and credible. It’s what leads to women working harder and waiting longer for promotion opportunities. It’s also a contributing factor in why they experience higher burnout rates. The trope advising her to work harder, while capturing a somewhat effective strategy for overcompensating for others’ high expectations, often causes women to continue operating in this mindset long after they’ve proven themselves to the point where they can claim full credit for their contributions.

The end results are harmful in the following ways:

- They exhaust themselves working twice as hard as they may need to, especially after the early stages of their career when they often have more demands on their time and energy than they did earlier in their careers.

- They train everyone around them to expect that they will work harder, achieve more and demand less than others, leading others to believe they enjoy the harder work and don’t need or want fair compensation in return.

- By adopting and perpetuating this mindset, women and their mentors who over perform set the bar higher for all other women, reinforcing the unfair advantage men who “work half as hard” receive when this trope is operating in the culture.

NEW TRUTH: Working twice as hard just earns you more work.

Having coached many female and under-represented leaders through the process of managing their time and energy against burnout while gaining visibility, credibility and influence, here is what I believe:

- You DO have to prove yourself

- You DO have to achieve and learn how to accomplish things that matter.

- And you DO have to work harder than some who enjoy the privilege of the benefit of the doubt when they underperform

It’s not fair. Unconscious bias is real. AND while you may have to work twice as hard sometimes, other times you don’t. In these situations, when you continue to over perform you’re only reinforcing others’ biases that make you martyr yourself for diminishing returns. Learning when to go the extra mile, when to conserve your energy and how to prioritize more stringently are good life and leadership skills to have no matter what your challenges.

MENTOR ADVICE: Help your proteges train colleagues to respect their time by achieving high-priority results (promotable work) in the time they have, and turning away low-value projects that don’t advance their goals.

Once they’ve proven themselves, before they’ve burned out, your mentee needs to switch focus from effort to quality and impact. She needs to work smarter, not harder.

Help your protege switch out “twice as good” for “smarter not harder” as soon as they can as their default work pace. Help them set others’ expectations that they will produce results that matter and manage their energy and time against their highest priorities. Help them practice goal setting and learn to define their own success by what they accomplish instead of how hard they work.

If you notice, yourself, that you buy into the “women must work twice as much” trope–for yourself or others–let your relationship with your protege challenge you to put this advice to work in your own career development and how you manage your team. Hold yourself, and others in your mentorship program, accountable if you find people over valuing the contributions of men who under perform, and lighten up on your expectations of women if they’re unfair. Having taken on the opportunity to mentor women you’ve also earned the right to claim credibility without burning yourself out. Don’t just give advice, become a role model to others struggling with the same challenges.

TROPE: Never cry at work.

Long ago, lost in the mists of time women were labeled as “too emotional” by the men that ran the world. Unsurprisingly, this cultural stereotype found its way into our workplace cultures through a belief that the office was the realm of the brain and the home was the domain of the heart and community concern. However, the cultural bias against emotional expression at work has been wielded as a cudgel against women, and men(!), penalizing everyone for emotional expressions such as crying while failing to penalize men for toxic expressions such as angry outbursts.

This cultural bias disadvantages both women and men, since a healthy ability to process and manage emotions is critical to human well being and effective leadership, regardless of gender or situation.

InPower Toolkits for Mentors and Protégés

NEW TRUTH: Emotional intelligence (EQ) at work is critical to success, and all authentic feelings are key sources of information.

Without re-litigating most of human history, let’s accept that in recent times many organizations and successful leaders have come to understand that emotions, and more importantly, emotional intelligence (EQ), are actually critical to business success. EQ is a key key skillset and can actually help us manage toxic emotional people and situations.

Emotions are not the same as emotional intelligence. At its core emotional intelligence requires that we have a healthy understanding of our own emotions, can read emotions in others and can use this information to make effective decisions. This requires as much authentic emotional expression as possible, including at times, tears.

MENTOR ADVICE: Help your protege master EQ to enhance her situational leadership skills and use genuine expressions of emotion, in herself and in others, as information sources to make better decisions.

When your protege is using emotional intelligence, her own emotions and the emotions of those around her (even crying, sometimes) provide information she can use to understand how to better influence others in the community and the situation in general. A key input to effective situational management strategies, the ability to read people emotionally and manage her own emotional landscape will help her manage her stress to prevent burnout as well as stress in her teams.

You may find that helping your protege build her EQ will challenge you to refine your own skills in this area. If you’re participating in a mentoring program, this is an important subject to bring up with other mentors to make sure everyone understands the importance of leveling up their EQ skills. Everyone in a mentoring relationship should appreciate the importance of balancing empathy for their protege with some insights into when “tough love” is the best approach. This requires you to become more nuanced in using emotional information to guide your advice. Lean into the opportunity and level up your own EQ skills as you’re mentoring women and you’ll find many opportunities in your work to deploy these skills to engage employees, manage conflict and build strong, trusting relationships more generally.

TROPE: If you’re not projecting confidence, you have Imposter Syndrome.

Women often struggle with the “Imposter Syndrome” as they climb higher in leadership. The Imposter Syndrome is a mindset of vulnerability that descends on women and men when they feel that others think more highly of them than is warranted. Specifically, it is the fear and anxiety of being “found out,” for the “fake that I am” and then feeling shamed and called out. It drives them to perfection with an unfounded belief that they should have all the answers. Often a result of their inner critic, the Imposter Syndrome can give the most capable and confident leader everything from butterflies in their stomach to panic attacks when taking on new, high visibility challenges.

Early in their careers, many successful young women feel confident because they are enjoying the successes and rewards of their work as individual contributors. Moving closer to mid-career when they gain access to management opportunities, things begin to change and fewer women than men advance into management. Reasons for this are complex, but Imposter issues are definitely a factor since many younger women don’t feel they know how to succeed managing others and don’t have a peer mentor community, role model, mentor or sponsor to offer advice.

It’s often when they are on the brink of the highest-level executive roles, when they need to project the greatest confidence in themselves and in the business as well, that they encounter the most deeply self-defeating Imposter feelings. At the point where they will have greater visibility, greater influence and “more to lose,” the voice of the Imposter becomes very loud, sapping their courage, encouraging them to play small, quiet their voice and—worst of all—shy away from risk, conflict, and competition.

Some women even follow this voice and turn down promotion opportunities they are qualified for, choosing to wait until they’re overqualified. Waiting to advance can set their career goals back years, depress their lifetime earnings and increase the likelihood they will encounter ageism bias later in their career, which can bar them from CEO and CXO positions.

NEW TRUTH: Imposter syndrome is not a condition, it is a crucible of professional and personal growth.

Men also experience the Imposter Syndrome, as do under-represented minority leaders. It’s a common human phenomenon when we’re in our stretch zone, uncertain about how to succeed doing things we’ve never done before, or in environments and situations we’ve never encountered. When we’re taking on new challenges we really are “faking it to make it,” relying on alliances and smarts to navigate our way until we succeed and own that success.

However, too often women experiencing an undermining inner narrative (often programmed from others around them since birth) believe that the Imposter is part of who they are at their core. Even some of the most accomplished female leaders believe that negative inner voice is delivering “truth” and they feel like they have some kind of “Imposter disease” that must be “cured” before it ruins their career. They don’t have enough support from mentors and confidants who help them own their success once they’ve achieved it, replacing the Imposter’s narrative with the Achiever’s narrative.

The Imposter’s voice should not become an integral part of a woman’s identity. With support she can learn to hear it as an ally, challenging her and pushing herself into new experiences that call on courage born of previous successes.

MENTOR ADVICE: Help your female protege gain a new perspective, viewing the Imposter as an ally that challenges her to master uncertainty and risk. Help her use her success to develop a personal brand narrative she can believe in.

Effectively mentoring women requires the mentor to understand that women seeking senior roles without a strong inner voice of courage, must build their own strategies to counter the Imposter from within. Good mentors can help them befriend their inner Imposter, letting it point them at areas they need to strengthen and insecurities they need to grow beyond.

It’s particularly important for women who overly focus on their inner voices of doubt to put energy into a mission-focused counter narrative they care deeply about. Women regularly go beyond their self-imposed limitations when they believe something important is on the line. As her mentor, you can help her identify the external mission that captures her imagination and pulls her so strongly towards success that she can let go of her anxieties about failure.

Mentorship programs can also leverage strategies to help mentors and mentees explore their stretch zones, becoming more comfortable:

- Setting specific stretch goals and focusing on building greater confidence one skill at a time

- Acting “as if” they’d already succeeded to bring their intuition and “gut” reactions to help them navigate uncertain and uncomfortable situations

- Leaning into the fears to dispel them, asking questions like “what would you do if the worst actually happened?” And “what would you do if you were not afraid?”

Most importantly, when women achieve success after navigating challenges despite their Imposter feelings, mentors can help them craft their success narrative. Good mentorship provides a strong success narrative recasts the Imposter’s anxiety as a stretch zone win, building her belief in herself while tackling other stretch zone opportunities in the future. Helping your mentee believe in herself and in her ability to grow and improve by taking on risky challenges is a gift that will keep on giving. As she owns these successes, her authentic confidence builds and she will be better able to pass on this gift to others she mentors in the future.

As you’re mentoring a female through Imposter situations, pay special attention to why you believe in her, and verbalize your genuine beliefs often to give her a counter-narrative to the Imposter belief she has that tells her she is fundamentally flawed. Resist the urge to label her as having the “Imposter Syndrome” as if it were a disease diagnosis and encourage her to see herself as courageous for taking on difficult challenges instead.

And for women mentoring women, female entrepreneurs and those investing themselves in improving female representation more generally, this topic is particularly important for you to explore. Virtually no one, especially female leaders, rise to the top without befriending the Imposter. And everyone deserves the chance to reframe the voice of the Imposter into the voice of an ally encouraging us to thrive in our stretch zone.

TROPE: Women are good at collaboration.

Women are typically acculturated to building relationships, often bearing the group’s burden of the emotional labor required to maintain them. As a result, women often do display strong collaboration skills in the workplace.

It’s important to note that relationship management and collaboration are not necessarily the same thing. In addition to requiring emotional intelligence and attention to relational dynamics, collaboration is goals-focused. Effective collaboration requires orchestrating relational skills along with prioritization, motivation, engagement, transparency, technical skills and many other strengths to achieve a targeted business outcome.This means that unless she learns to apply her relational skills to achieve high priority outcomes, a woman’s culturally nurtured interpersonal skills do not always advantage her in developing an effective collaborative style.

In addition, collaboration is not always the most effective management style needed in every situation. Sometimes it’s more impactful to be decisive and direct, given the circumstances. The best leaders know how to read situations to determine whether to deploy relational collaboration skills or directive approaches in order to deliver the desired result.

NEW TRUTH: Women are good at all kinds of leadership.

Other than being more likely to be rewarded for emotional intelligence than men in most cultures, women are no more naturally skilled at all the strengths required for balanced situational leadership than men. Learning to round out their innate strengths with a full complement of situational management skills is a journey every leader must take, women and men alike.

However, when women master the skills of versatile and responsive leadership–across the spectrum of collaborative and directive styles–they can actually reap rewards greater than the men around them, benefiting in both promotions and salary.

Helping women view their relational skills as strengths to build on (instead of rest on) can help her see opportunities to grow in her stretch zone. She can set her sights beyond “being good” at collaboration to mastering collaboration and directive professional styles, both.

MENTOR ADVICE: Help women become good at all kinds of leadership.

Part of mastering situational leadership, knowing when to collaborate and when to direct, all leaders excel. Effective mentorship helps her spot her comfort zone on the spectrum between relational and results-focused leadership. It helps her identify her stretch zone, learning how to be more directive when appropriate or collaborate effectively, based on the situation.

Not sure how to evaluate where she is on the spectrum? Suggest that she conduct a Leadership Circle Profile 360 review for detailed data pinpointing her strengths and challenges in both relational and task-focused management skills. This program will give her specific insights into where she can focus her development energies, with your mentorship support.

Use this frame for yourself and your teams, too. You, too, exist on the spectrum of management styles and have a comfort zone and a stretch zone. Particularly if you want to work on your relationship skills, use your mentorship efforts to gain more practice!

TROPE: Women are uncomfortable with risk.

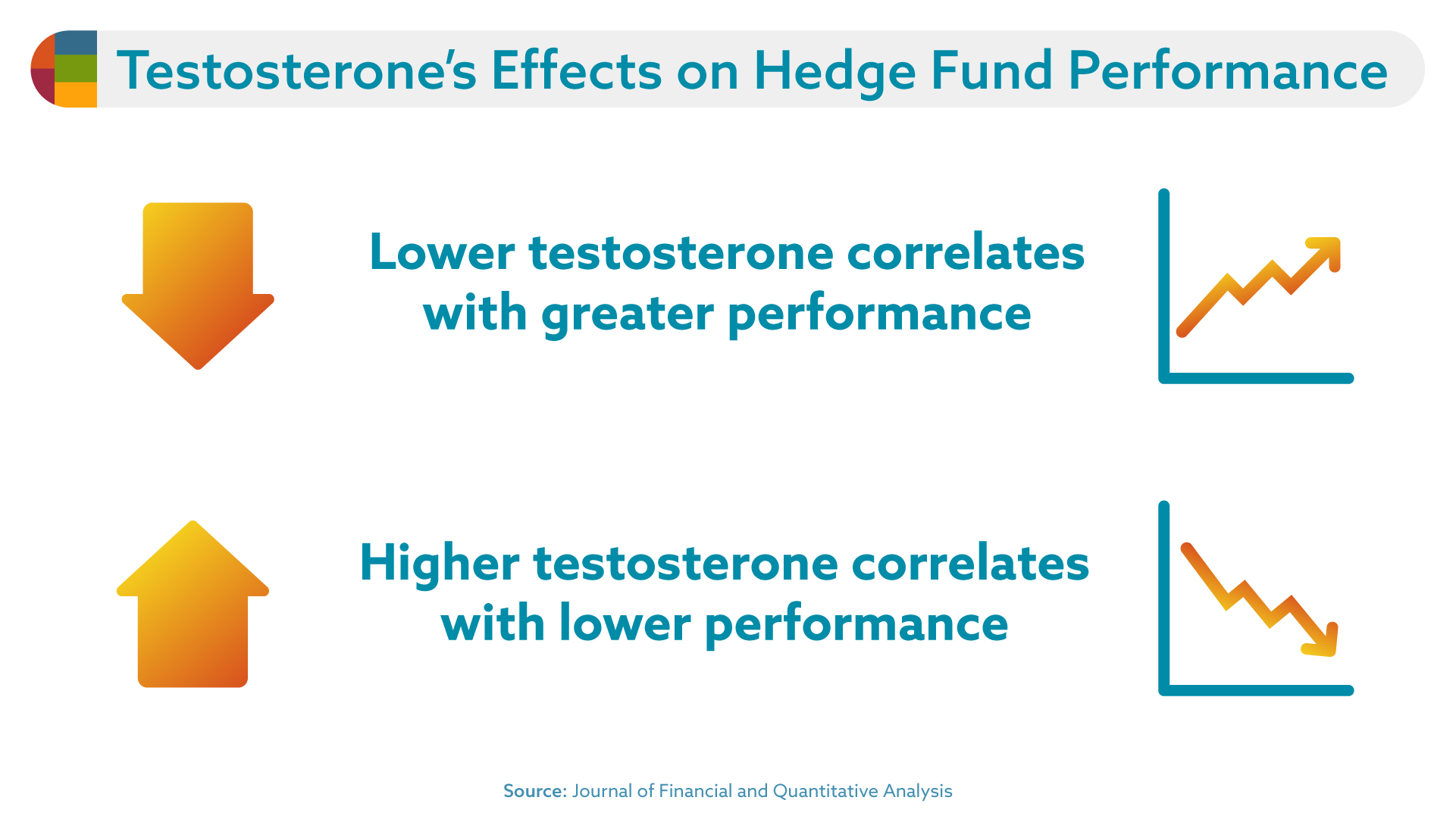

It is commonly believed that women do not like risk. This unfounded belief about women in the professional setting is often cited as a reason for not “taking a chance” on them for executive roles, which generally require a high tolerance for managing risk and uncertainty. It’s also ironic because women are, in fact, no more or less effective risk takers than men, and often succeed in producing results because of their good judgment in evaluating risk.

One distinction that sets women apart from their male colleagues in risk management is that rather than taking unfounded risks fueled by overconfidence and bravado, women are more apt to do more research before placing a bet in decision-making. Women are more likely to mitigate risk by seeking incremental, and consistent, reward. This may be because they believe (with good reason) that any bad risk they endorse will reinforce biases against them and be used as excuses for sidelining them and penalizing them. In this sense, risk-taking is a higher-risk career strategy for women than it is for men.

NEW TRUTH: Women are comfortable with considered and managed risk.

Regardless of the reason, women appear to be better “considered risk takers” than many male leaders who have been rewarded for taking unfounded risks and encouraged to “go big or go home.” As a result, it’s common for women and men on teams to overcompensate for each other’s “tortoise and hare” approaches to risk.

There is obviously a role for both conservative and aggressive risk-taking. Good mentorship will help women balance when it’s important to heavily research risk to go in eyes-open while also playing the high-risk/high-reward game that often leads to success.

MENTOR ADVICE: Help your female proteges understand their relationship with risk and learn to manage necessary risks.

A female leader who seeks higher levels of leadership, especially executive suite and board appointments where every decision involves risk, must counter the tendency to be painted as someone who only takes safe risks and is uncomfortable being audacious. They will benefit from a comfort level with risk that balances daring and considered risk. They must also take enough bold risks that pay off through their career so they can prove to a sponsor or hiring manager–who wants to take a risk on them–that they are a good bet. The most senior leaders seeking employees for sponsorship often look at how up-and-comers manage risk to target those they wish to champion. As her mentor, you can help your mentee understand that mastering risk can give her access to a sponsor’s attention.

When mentoring women, help them understand their comfort zone on the spectrum between conservative and impulsive risk-taking in the decision-making areas that will mean the most to their professional success. Help them find their stretch zone and focus their development in this area. Also, help them speak to their relationship to risk so others see them as comfortable evaluating and managing risk appropriately.

Use your experience mentoring women into a successful relationship with risk as an opportunity to evaluate your own. Don’t confuse bravado-infused, impulsive risk-taking with risk management. Think it through and be as bold as you should be under the circumstances, making you a good risk role model to everyone you influence.

TROPE: You need “executive presence” to break through the glass ceiling.

Even the most executive-minded of my clients often find one piece of advice their mentors and supervisors give them befuddling: the advice to work on their executive presence. While executive presence for women is common career advice, it is usually code for intangible aspects of professional styles established by, and biased towards, male behavior. Thus, for many the lack of specificity in this advice often confuses their ability to figure out how to advance.

To add to the complexity of this issue, presence in the executive suite goes beyond style and incorporates mindset, belief in oneself, the ability to instill confidence in others and clarity of communication. It also tends to incorporate the ability to manage priorities at both the strategic and tactical levels in situationally appropriate ways.

NEW TRUTH: “Executive presence for women” is advice that unconsciously incorporates male stereotypes, which become a pillar of the glass ceiling.

Different kinds of people have different professional styles, expression and presence, women in particular can struggle to code switch into the stereotypical (male) management style others expect in an executive leader. For example, where men are often rewarded for an aggressive style, women are far more apt to be penalized. You’ll observe this unconscious bias when both men and women describe an accomplished female leader as “a bull in a china shop” and for this reason is “not a good cultural fit for our company or executive suite, even though she produces results.” This dynamic often leaves women leaders in a double-bind, penalized for the same behaviors their male counterparts receive rewards and recognition for, and it’s a particularly challenging road to navigate, especially since they typically have fewer female role models to guide their professional identity development.

Women who successfully navigate past these stereotypes into the executive suite often earn their way into the C-Suite and board positions with a personal brand reputation built from a combination of:

- results

- an executive mindset

- emotional intelligence

- authentic confidence

- the ability to motivate others

- allies

- boundaries

Many struggle to understand and cultivate this kind of personal brand presence because they are not effectively mentored or coached into it, including by other senior women who did not receive such mentoring. Their education also does not tend to include insights into these less tangible aspects of strategy. Men, on the other hand, through role modeling, informal mentoring and development opportunities, are more likely to be supported in developing their executive presence and personal brand by other male leaders. Thus it’s more typical that men are groomed to fit into the corporate cultures already skewed in their favor.

In fact, many women are mentored and coached early in their career towards behaviors and mindsets that are the exact opposite of the executive mindset. They are rewarded for getting the details right, and they are penalized for taking strategic risks and claiming responsibility for their own successes in ways many men are not. Women are told they must work twice as hard as men and that their hard work will be recognized and rewarded with advancement. Thus, most women believe that their success will result from hard work, an attention to detail and extreme humility. While these traits often work through the journey of middle management, unfortunately, these are not characteristics (by themselves) that characterize successful executives who can:

- break away from the details to see strategic possibility

- manage workload (their own and their team’s) in realistic comparison to their priorities

- demonstrate courage amidst uncertainty and risk

MENTOR ADVICE: Move past your own stereotypes about executive presence for women. Focus on helping your protege gain an executive mindset and produce results that demonstrate her readiness for an executive role.

This area should prompt every mentoring program and mentor (female or male) to stare deeply into the mirror. If you find yourself struggling to help your protege understand what elements of her professional style or personal brand may be holding her back from advancement, begin by interrogating your own stereotypes and biases about what a female executive should look like and act like.

The goal of such introspection is not to make yourself (or your program) feel bad, but to parse out what aspects of her challenge are due to (a) her own need for development, and what aspects (b) require you (or your program) to help her navigate cultural biases, including and related to your own, which are stacked against her.

If mentors and mentoring programs do the difficult work of parsing out development vs. bias challenges with her, don’t be surprised if you both feel helpless to change the culture. Cultures are notoriously hard to change. The good news is that culture change happens smoothly when people succeed in ways that are aligned with the highest cultural values but demonstrate alternative ways to deploy them to create success. This helps agents of change evolve the culture from within rather than challenge it aggressively, which is a recipe for failure.

Here are two ways I often coach and mentor women and program leaders to develop effective executive presence in ways aligned with the culture. While each mentee will need unique advice, I consistently observe two areas that are under-communicated to women. As they develop their abilities in these areas, they often step up their game to navigate others’ biases without becoming confrontational:

- Learning to operate at the strategic treetops and the tactical weeds, as appropriate and to manage her own energy/workload and the energy/workload of the organization against top priorities

- Building on her belief in herself to project belief in the business and view confidence as a skill helpful in motivating others, mitigating risk and engaging stakeholders

TROPE: Women should “just ask” for a raise to close the pay gap.

Traditional workplace culture myths about why women don’t climb to the top as frequently as men assert that whatever reason she’s not getting ahead is her fault, which she has to fix. This is the dynamic behind a lot of advice women receive to work on their executive presence, assertiveness and visibility. And of course, there is always some truth to it. Everyone must continually improve themselves, grow and take on new skills, styles and mindsets to succeed at higher levels. Everyone has deficiencies to overcome in order to ascend into greater responsibilities and authorities. However, for most women determined to make it into senior positions the “just fix the women” trope is exhausting.

Many of these situations are hard to parse out as gender discrimination. Men often find themselves bumping into barriers to success, too, so where can well meaning mentorship programs look for specific situations to update people’s thinking and equalize the burden on the women and the cultures to change?

Here is a trope that desperately needs updating. “Women don’t ask for raises, promotions and opportunities to prove themselves” is a trope often cited as the reason women don’t receive equal pay and career development opportunities. And of course, when it’s true that a specific protege is deserving but uncomfortable advocating for herself, her mentor must encourage her to speak up. However, mentors can also be on the lookout for times when the protege is doing everything right and still encountering inequitable performance requirements and discrimination.

NEW TRUTH: According to research women actually do self-advocate and ask for raises, but they encounter systemic biases and barriers to pay equity (which men don’t) that make their requests less effective.

Research shows that women do ask as often, but don’t receive pay increases as frequently as their male counterparts. In fact, there is evidence that often when women do advocate for themselves, they are penalized and told they are not being a “team player,” are told the “time is not right,” or simply ignored.

There are undoubtedly many biases that conspire to create this situation, including:

- The biases towards feminine agreeability, while depressing their wages, makes many see women as “aggressive and selfish” when they’re actually being assertive if it has the impact of rocking the boat, confronting uncomfortable truths or advocating for themselves

- The biases that make us recognize and reward male characteristics in our leaders while also blinding people to the ways women lead effectively in non-stereotypical ways

- The biases that make people believe men should earn more to take care of their families as if a woman’s financial responsibilities to her family is not equally important.

This is unfair to individual women, but it operates on a societal scale as well. The biases that perpetuate this myth of deficient self-advocacy, can make us believe the gender and racial pay gaps are the under-represented leaders’ fault when it’s not, thus perpetuating inequity and removing responsibility from the culture to address it.

There is a point in many women’s careers at which they find themselves jumping through hoops over and over again, working harder, rising to greater challenges and accomplishing more than everyone around them, requesting promotions and pay raises only to be told it’s still not enough and they must just prove one more thing… The goal posts keep moving farther away and any self-respecting person would feel she has little choice but to walk away and try to find a culture fit for who she is instead of some impossible-to-achieve, and exhausted, version of herself.

At this point, when your mentee is doing her part but the culture is holding her to unfair and inequitable standards, the mentor’s advice must shift beyond self-advocacy to organizational influence.

Bottom line advice for women who hit this point: learn to negotiate around bias and discrimination—or leave.

MENTOR ADVICE: Help your protege identify inequitable performance standards and develop strategic responses.

As someone with less organizational visibility, your protege may not be in the best position to determine what is inequitable treatment and what is a development opportunity for her to grow. As her mentor, while there are no easy answers, you may have greater insight into how fairly she’s being treated and how she can grow to manage her situation. Your job is not to decide who is at fault, but to do what you can to help your protege navigate company policy and practice, conflicting cultural values and confusing bias as well as her own developmental potential in order to receive fair compensation and recognition. For those running mentorship programs, you also have the responsibility to help both everyone involved understand these dynamics.

This requires that you be fair-minded yourself, assuming there may be opportunities for both the organization and your protege to behave so that she may receive the rewards she deserves. For example:

- women can position themselves for advancement and raises as opportunities to build alliances, hone their persuasion and influence skills, practice negotiation and self-advocacy

- organizations can take steps to audit their pay grades, promotion and raise criteria, manager training and advancement approval policies for signs of discrimination and bias

Most importantly, as her mentor, you must respect your protege’s perspective. Do not tell her she’s imagining things even if you believe her perspective is skewed. Instead, help her see what is within her control to change regarding her visibility and results. Help her strategize how to influence those who control her salary and position. At a minimum, acknowledge the possibility of bias making her struggle harder than her male counterparts and if she chooses to pursue anti-discriminatory cultural change, don’t desert her.

Of course, you can do more than this. You can go to bat for her openly, as her sponsor and her advocate. Even more personally, you can interrogate your own biases to discover whether you believe a man with the same assets and outcomes should be rewarded more than she is. If you learn that you have biases, don’t turn away or feel guilty; simply update your assumptions and stereotypes and invite colleagues and other leaders to do so as well.

TROPE: Manage stress by achieving work-life balance.

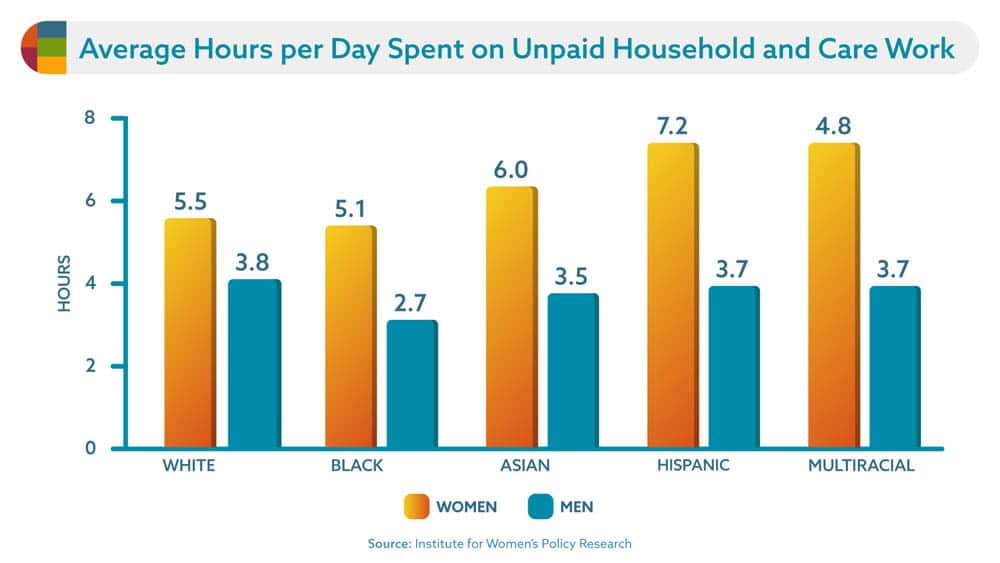

The pandemic has brought long-held inequities between working women and men into sharp relief, demonstrating the extra burden women hold in caring for children and the home (approximately 2 hours a day more for women), in every age and ethnic category, whether they work outside the home or not. Study after study shows that both women and men believe it’s appropriate for women to handle more “invisible work” at home.

This social expectation extends to the workplace as well, primarily in the form of “non promotable work.” Workplace biases that view women’s contribution to non-promotable work as more important to the team than men’s contributions place an unfair burden on women, while freeing up men to focus on tasks that will advance their career.

Particularly in American households, married women spend nearly twice as much time on household and child-related tasks as their husbands. Finding effective ways to meet the demands of a professional life and a personal life is a challenge every working person juggles. However, the higher everyone goes, the more often it becomes a requirement of the job for one’s professional demands to take higher priority than personal ones. Sometimes this is a result of unhealthy, workaholic business cultures, but it’s just as often a reality of executive roles, because the most significant problems tend to roll uphill, escalating to more and more senior leaders, seeking someone with the authority to fix them. By the time these problems get to the top, they are often at the critical stage and require urgent attention so as not to put the business itself at risk. These five-alarm-fire business problems do, then, tend to overshadow all other priorities (business and personal) by the time they land on an executive’s desk, even if it’s dinner time or on the weekend.

Women more often struggle with work-life balance because they, their colleagues and families, have acculturated to the assumption that women should take on the invisible work of the default fixer of personal challenges while men are the default fixers of business challenges. When she’s aspiring to an executive role, then, she’s usually trying to be seen as a reliable fixer of business challenges while also meeting her own (and others’) expectations that she will be the reliable, default fixer of personal issues as well. This problem haunts single and married women, mothers and non-mothers alike. For mothers, however, there is no getting around the additional physical requirements that birthing and caring for young children puts on them when babies come into the world.

While men find work-life imbalance a challenge to navigate just as women do, men find more cultural forgiveness when they drop a ball at home, and they also pay a lower price at work. This social inequity leads more women into a no-win scenario between overwork and burnout.

NEW TRUTH: Negotiate for work life equity.

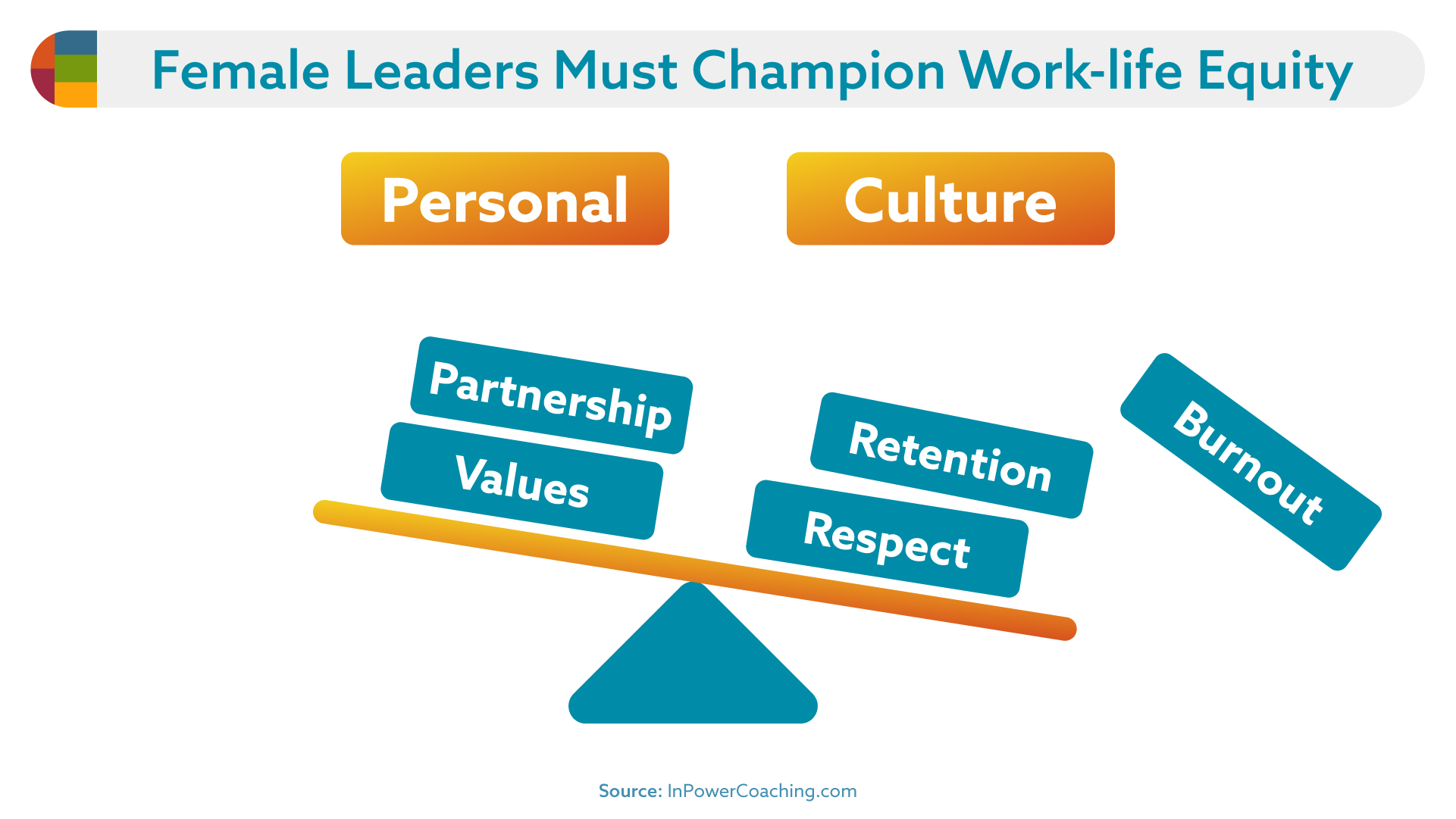

While everyone wrestles with work-life balance issues, it’s a disservice to men also to frame it as a uniquely female problem. In fact, the typical work-life balance dialog obfuscates the fact that juggling personal and professional demands is both a personal challenge to negotiate obligations between partners and external support relationships as well as an organizational challenge to retain productive and capable employees (of all genders and family structures).

Even though home life is more egalitarian than it used to be, women working are still expected to carry more of the burden at home, leaving them less time and energy to take on more responsibility at work. The results of these inequitable expectations are that if a high potential woman does not have a supportive partner or family, she is much less likely to be able to make it to the top without compromising either her home or work commitments.

The truth is that for many families, managing a healthy home situation and rising into the executive ranks don’t always mix. This may be why female CEOs divorce more often than male CEOs. Those women in leadership positions whose families stay together often have supportive partners and communities, who can handle family obligations, and provide other forms of “reliable backup” at home.

Without equitable workloads at home and in the office, promising high-potential female talent will burn out. When women establish career goals to gain more senior roles, they must become proficient at gaining recognition while negotiating workplace biases, which places an unfair burden on their performance and leads to inequity in their workloads. They must also negotiate equitable responsibilities at home so they maintain the energy to perform at work.

MENTOR ADVICE: Help your mentees understand where their “non-promotable” workload unfairly burdens them, relative to others in their life and work, empowering them to negotiate for equitable work-life responsibilities

At the end of the day, for your protege to rise to her full potential in her work-life, she must negotiate her personal and professional partnerships so she can be available to handle the five-alarm-fires at work even as she meets her personal obligations in accordance with her values. She must also be able to manage her own energy reserves to prevent burnout at home and at work.

As her workplace mentor, you must be careful advising your female protege about her home life situation and values. However, it is very appropriate for you to do the following:

- help her understand what “promotable work” looks like in her organization and how to negotiate to take on “only her fair share (and no more)” of non-promotable work

- help her see that as a woman, she may be challenged by workplace, personal and societal expectations to take on more invisible work than is healthy or fair

- encourage her to learn to advocate for the support and boundaries she needs everywhere in her life, which will allow her to meet her workplace performance requirements and her personal commitments

As with all other cultural conundrums you and your protege may face, this is also an opportunity for you to explore your own biases and stereotypes about how much invisible and non-promotable work women must do to be seen as “team players.” This is a good opportunity for you to rethink how much responsibility you believe women should carry for being “the fixer” at work and at home. It’s an opportunity for you to think less about what any one individual should do to “balance” their home and work obligations and more about what family and work systems can do to allocate the work to be done equitably to preserve everyone’s energy for true priorities.

TROPE: Women face extra pressures and may opt out of promotions to protect themselves

There’s a trope that says women become less committed to their professional lives once they become mothers or enter their childbearing years. Research shows this to be patently false, as both men and women are equally committed to their work and also express similar concerns about maintaining work/life balance. Similarly, it is often stereotypically assumed that when women have children, they leave the workforce or exit their career paths. In a healthy, pre-pandemic economy, this was most often not the case.

Post-pandemic, life for women is more complicated. While there’s no evidence that women’s commitment to their work suffers, the reality is that more women experience extra stress from the burdens of uncertain child-care and resultant increases in burnout.

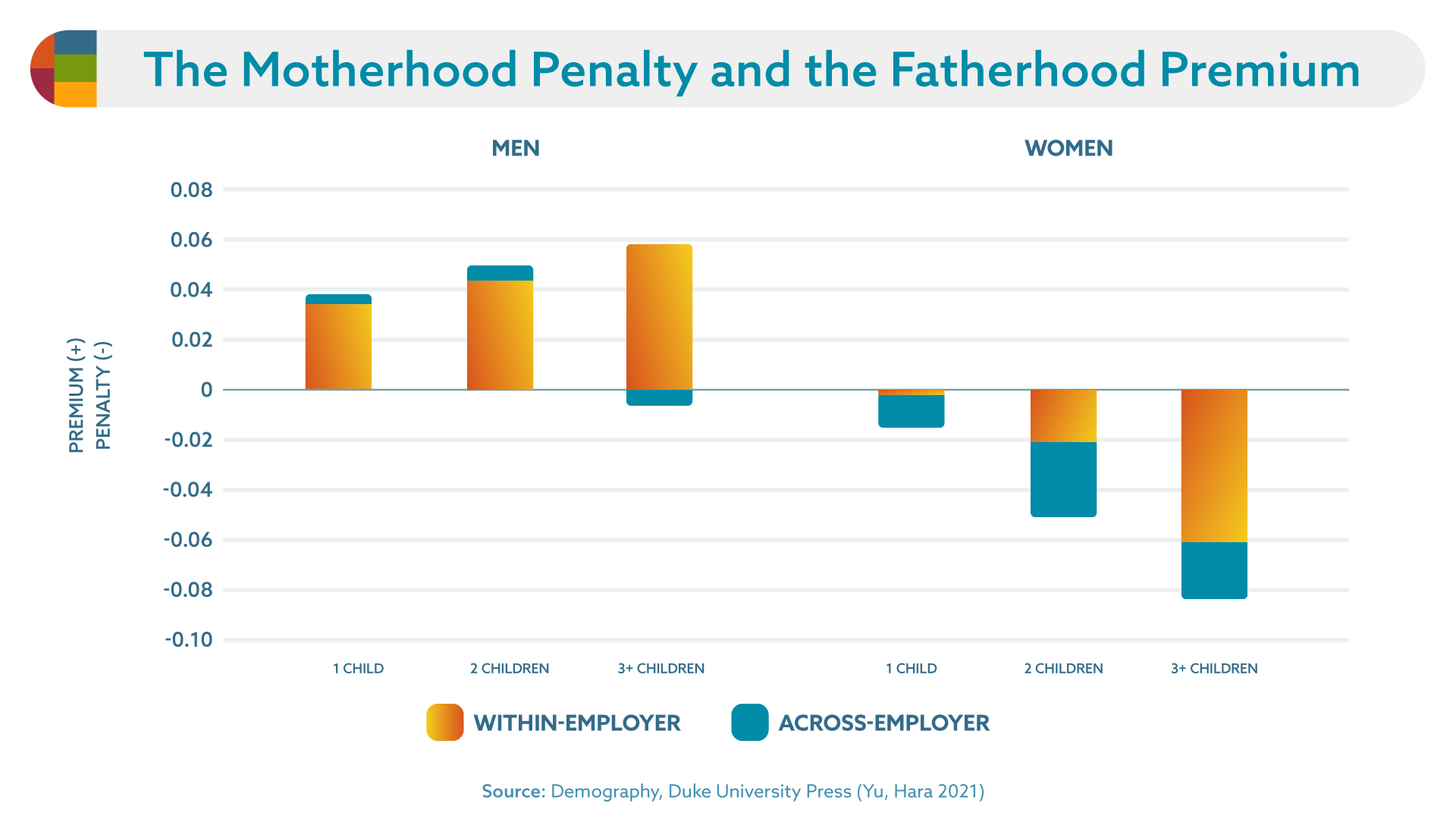

The stereotypes themselves create very tangible inequities for women, especially when they choose to become parents. These inequities manifest as differing societal expectations, organizational norms and systemic structures at work. For example when people become parents, juggling midnight feeding schedules and daylight report deadlines:

- men are told (implicitly and explicitly) to “man up” and find ways to make it work, but they receive a “fatherhood bonus” with preferential treatment as compared to single men and other women

- women, however, experience a “motherhood penalty,” offered reduced pay, fewer promotions and negative perceptions about their loyalty as compared with men and single women

Given the litany of biases that hamper women’s path to leadership, combined with the realities of differential treatment and burnout, there is no question that women face extra pressure to make personal compromises in order to level up into the the executive suite. It’s no surprise that some women simply opt off the high-potential track, or quit, as a way of escaping what they may perceive as a no-win scenario.

InPower Toolkits for Mentors and Protégés

NEW TRUTH: This trope is more true than ever before, but women don’t need other people limiting their career choices under the guise of “protecting them.”

While these extra pressures are unfair for women and men alike, the worst part for women is that well-meaning people sometimes generate additional barriers “for their own good,” sometimes without their knowledge. Instead of learning about challenging positions, women often find out after the fact that someone removed their name from the high-potential list to save them the stress of having to prioritize balancing a career opportunity with personal responsibilities. Whether due to unfair bias or good intentions (or both), ostensibly well-meaning superiors, mentors and sponsors shunt young mothers and women facing personal pressures to less demanding roles on the assumption they need some slack at work to free them up for more time at home.

Instead, truly well-meaning leaders have the opportunity to mitigate against female employee turnover by adjusting flexible work arrangements and performance requirements to enable high-performing women to contribute value without burning out. At a minimum, they must make sure women are given the career choices they have earned. Empowered with choice, women can protect themselves.

MENTOR ADVICE: Women and their mentors should look at all their options together, and her decide.

As her mentor, your protege can use your support in strategizing around the very real and demanding expectations that her colleagues, friends and family have for her. Be wary of trying to protect her from inequity and overcommitment. Instead, commit yourself to believing in her and helping her believe in herself. Help her understand what is fair and what is unfair. Help her parse out her choices and options, including the possibility of negotiating her obligations at work and at home to build the career and the life that she wants.

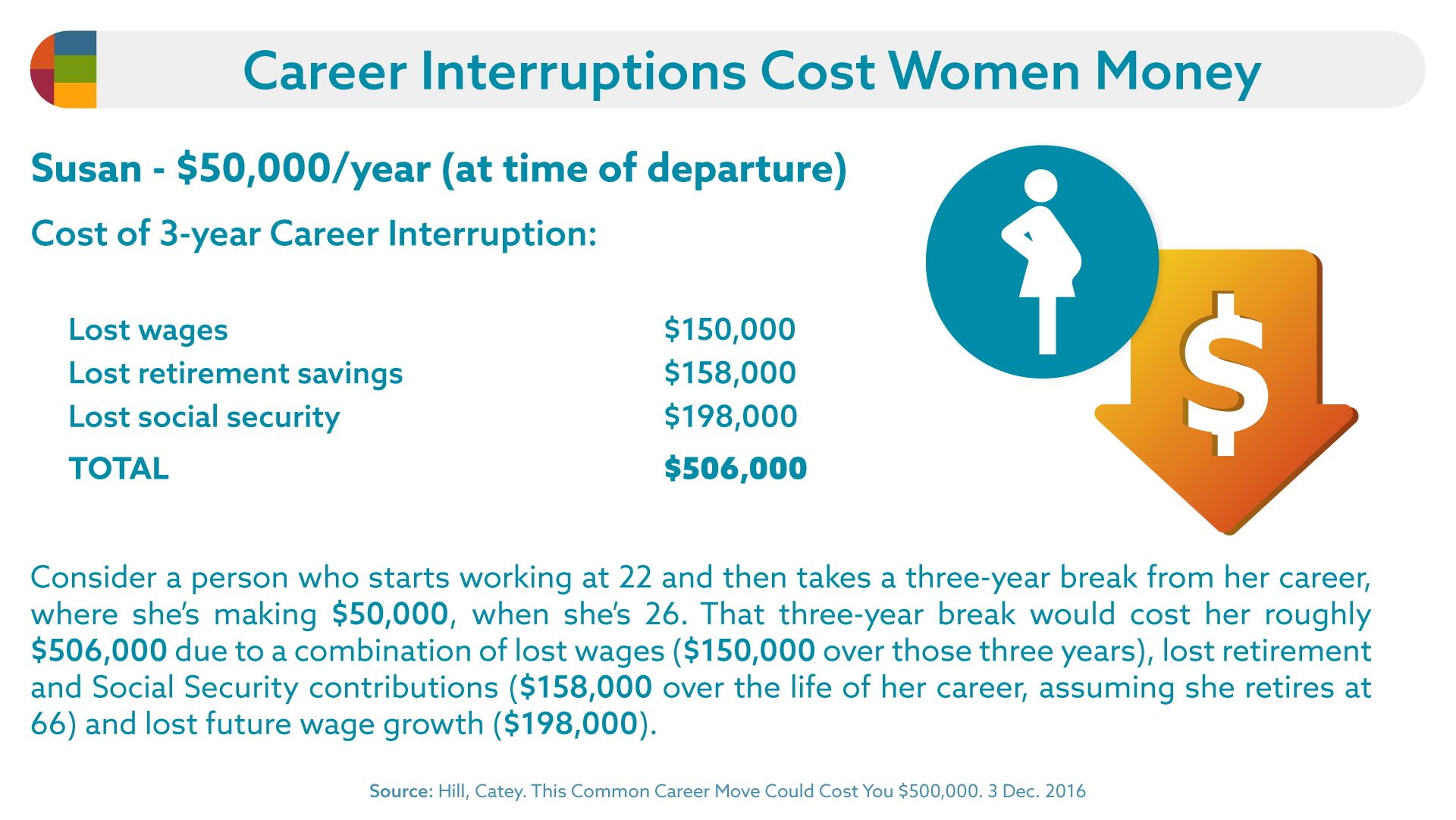

Help her understand that even if she opts off the professional development track to prioritize personal obligations for a while, she can and should do so in ways that give her an onramp back to higher levels of impact if/when she chooses to rev back up in the future. For every year her career stays on track, she and her family become more financially secure.

While she may still decide to opt out, you do her a service by informing her and empowering her to decide for herself what choices best line up with her values and needs. By doing this you offer her the possibility of sustainable and healthy long-term success.

Take the opportunity in helping her manage around these no-win scenarios to explore your own tendencies to protect your protege or others you seek to empower. Challenge yourself to guide her in making the most informed and empowered choice possible. Whatever she decides for herself, accept it. Don’t view her informed decision to opt out as weakness on her part or failure on your own.

Mentor: Uplevel Thyself

The tropes above are just a few of the realities women in the modern workforce face when they set their sights on leadership roles (learn about many more here.) As her mentor, you are in a unique position to help your female protege become more aware of the challenges she faces, and help her empower herself to explore her options.

This is true even if the situations you faced were different, or if you made different decisions in similar circumstances.

When mentoring women you have the opportunity to uplevel yourself as a leader. When you get curious about your protege’s experiences that are different than yours… when you explore your own biases and challenge yourself to move beyond them… when you open yourself up to growth that will make you a better leader… everyone benefits.

Download a 1 page PDF summary of these tips and receive this advice in PDF via email.

Guide to Women in Leadership

Organizations with women in their executive suites regularly out-perform others. Yet rising female executives (and their mentors) are frustrated at how hard it is to break through the glass ceiling. In this extensive guide, Executive Coach Dana Theus shares her tried and true strategies to help women excel into higher levels of leadership and achieve their executive potential.